Lord of the Flies (1963)

Following a plane crash a group of schoolboys find themselves on a deserted island. They appoint a leader and attempt to create an organized society for the sake of their survival. Democracy and order soon begin to crumble when a breakaway faction regresses to savagery with horrifying consequences.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

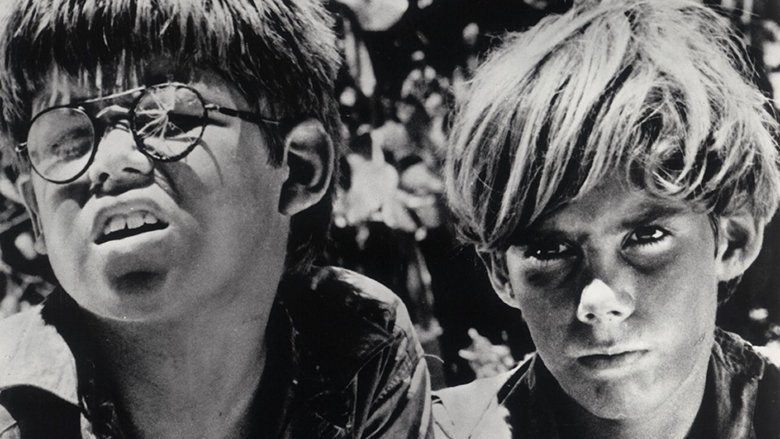

"Sucks to your asthma!" Fine adaptation of William Golding's classic novel. I'll forego summarizing the story since anyone who ever went to high school has read the book. I hadn't seen this film in years and was quite taken with how naturalistic it felt. It had almost a documentary feel to it. I was also taken with how little dialogue there was and how much of the story was able to be told visually (an albatross around the neck of most literary adaptations), which is why director Peter Brook's adaptation remains the best film version of this novel. The boys in the film seem very real and all seem to genuinely enjoy their time on the jungle playing with spears, making fire, and hunting. With the exception of the boy who plays Ralph, none of the boys went on to make any other films, which leads me to think that to a degree they really were just a bunch of kids in the jungle going feral. The central conflict between Jack and Ralph is portrayed well by both actors, who are sincere in making their cases for civilization vs. going savage, but I think the boy who played Piggy is the most memorable. He carries himself like a little adult, out of place and clearly seeing the reality of their situation; that he's out numbered, without any influence, and is at the mercy of the mob. This film works both on a subtextual level about human nature in terms of civilization vs. savagery, but it also works as a simple surface level adventure story. Overall, this is fabulous filmmaking and is a must see.

Fifty some years later, this Golding film is a reminder of the bankruptcy of England's understanding of itself. As one of the 3-4 greatest colonial countries of post-Middle Ages Europe, we would think the genocidal policies of Europe in various "new worlds" would have caused educated, intelligent people to ask questions about that history. Here we have an England that slaughtered and conquered and enslaved Africans and inflicted incalculable damage on Caribbeans, North American indigenous, Australian indigenous, and Asian cultures. But in this film book of 1954 and film of 1963, neither Golding nor Brook can see the way clear to including a single child of color. Why? Because apparently the issue of genocide and centuries of terror is a matter for white folk to decide.The Golding story is a British bourgeois wet dream of the failure to "civilize" the savage world, enacted of course by all white historical actors.To be precise here, Golding imagines here and in other works that there lurks in the uncivilized a murderous savagery that can only be corralled by western civilization. Regrettably, western civ has been too weak, too uncertain, and too incompetent to truly finish the world-caging task.Had Golding, and Brook, read something besides British self-congratulatory histories and seen something besides white "civilizing" westerns, they might have noticed that the true savagery of the last 600 years, or even last 2500 if we want to be a little comprehensive, originated in Europe. Always. And then Europe proceeded to genocide the world, only to find in 1930 the chickens had come home to roost. That the evil inherent in European supremacist values and social structures had faced off in Europe's very viscera. It refined its millennia of fascist practice and proceeded to genocide itself.That history, that euro-characteristic of supremacy -- supremacy of religion, of color, of culture, of gender, of values -- was the cause of it's even as yet unrestored, unreparationed evil. The very conception of The Lord of the Flies is a confident moralizing that at least a couple of white euro-men know the secret of evil. When, at least in 1954 and 1963, they hadn't the vaguest clue about their origins, but were in fact, stranded boys wandering in the arts, perpetuating the mythologies that wove back at least to "renaissance" Europe, or to fascist Rome, or to hypocritically un-"democratic" Greece, and indeed to the whole notion of "civilization" itself.It would have been instructive if Goldling and Brook had at some time tried to research the deep history of human tribes, how we lived for 40,000 years before the urbanization, which we call civilization, began. It was certainly the rulers and thinkers and "artists" and armies of "civilization" that destroyed tribes where ever they went. Perhaps, had they listened, they might have learned something about what it means to be a be a human being on this planet.

Seeing Lord of the Flies on film, I am struck by how unfaithful these screen counterparts are compared to the imaginary characters built up in my head from reading Golding's novel. They are tiny little things, barely even pubescent, and thoughts of savagery and bloodlust seem so far away. The novel's message is even more piercing when considered in this way; how easy it is to forget that these are the same little boys that descend into animalistic urge and desire later. Golding's words might have lulled some into complacency over the course of the chapters, but here there is a constant reminder through their pudgy limbs and wide eyes (and, to some extent, their English accents, which they recognise themselves as being the hallmark of civility and order). This low-budget feature version was shot by Peter Brook entirely on location, utilising all the harsh wilderness of the beach territories of Puerto Rico. The cast were all amateur actors, boys freed from authority and let loose to play on a deserted island. The style, a jagged combination of harsh natural lighting, sudden cuts and black and white images, saps the beauty from what should look like a holiday destination. The most frightening scene of the movie signifies the complete and utter abandonment of reason for savagery - when the boys gut Simon by the fireplace during nighttime. The cinematography continually throws the shots in and out of focus, one moment the white flames in sharp contrast, the next dancing chaotically in the background. And the hand-held camera bobs in motion as if it was one of the frenzied boys itself, chanting and getting right up into the painted faces of these savages. There are no light sources other than the fire and the bright spots of their torches, and in the darkness they become a trembling, murderous mass, more inhuman than human. Brook's rudimentary approach comes alive in some instances, and yet in others grounds the story. Most of Golding's figurative language is marred here; the painting of the island as firstly a wondrous paradise and then a nightmarish backdrop for ghouls and beasts, the forest as a teeming, dense thicket hiding the horrors of their imagination, even the palpable heat and scent of the island that the boys begin to be imbued with. The images wield darkness and shadow well, but the tribe become decidedly less menacing when they have to chant in open daylight. Golding's central allegory, of the beast and innate evil inside us all, also somewhat fades. Yes, there are grisly closeups of the rotting pig's head anointed with flies, but Brook ditches Simon's stumbling into surreal realisation, the horror of discovering something more terrible than any corporeal beast could ever be (unusual considering Brook's prior work in experimental theatre and Dali). The overall result is something like a strained documentary, trading periodical rawness and cynicism with stilted action, delivery and accents. It doesn't grip you like it should because there is still an undercurrent of rehearsal and civility under it, like a performance of a primary school play. Now, the 8mm murder mystery film that the boys shot themselves as they were acting out actual savagery? That I would like to see, because it would come from their own unplanned urges. And I wonder, of course, what quarrels might have occurred on that set, and who wrested directorial control from whom.

Well, this movie surely raises a bunch of eyebrows. I, being an eighth grader with an abnormal vocabulary and high reading level, was confused with both the novel AND the film. I understood the book more clearly because I saw all of the similes to religion and whatnot, while the film was being too artsy. I give the book a 7.5 while the movie deserves a 6. I also wouldn't mind a few asprins, too, since, I've got to say, am not used to watching black and white movies a lot. I did not enjoy it since it also left out quite a few parts, and I didn't enjoy how Piggy died, while he did die like that in the book, just did not appeal to me. I do not recommend this to anyone under the age of 12.