Arabian Nights (1974)

The final part of Pasolini's Trilogy of Life series is rich with exotic tales of slaves and kings, potions, betrayals, demons and, most of all, love and lovemaking in all its myriad forms. Mysterious and liberating, this is an exquisitely dreamlike and adult interpretation of the original folk tales.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

There's a lot of potential moral quandaries associated with this movie: real animals getting killed, disturbingly young actors engaging in simulated sex acts, some unsettling adult themes and the general feeling of heat and stench conveyed by the flies and sweat. Then there's Pasolini's signature shaky camera-work and rough acting from non-actors. If you can get past the thirty minute mark, and a few boring sequences, you may find yourself like I was charmed enough by its incidents that you keep watching to the end, waiting to see what surprise lay in store next. It features some wonderful moments that suit the mythical source material, and as plentiful supply of penises there ever was, certainly if you count unique penises, I reckon this could beat most pornos, if that's your cup of tea. They're normally just sitting there, bear in mind, but often they're doing other things. Not exactly family fare, but for those seeking a bit of weirdness, this may just hit the right spot. It would probably be hilarious if dubbed over Kung Pow style. (Or What's Up Tigerlilly style if you prefer).5/10 for me.

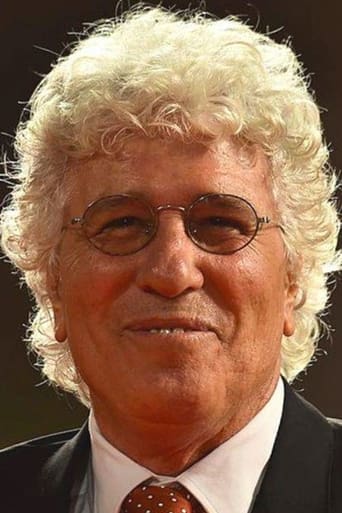

Resembling something out of an obscure dream, the characters from the ancient tales of the 1,001 Nights come to life in a dizzying spectacle of natural beauty, natural light, and the most breathtaking landscapes ever committed to film. Sumptously filmed throughout the exotic locales of Yemen, Ethiopia,Iran, and as far as Nepal, we are introduced to the story's hero, the sweet and innocent Nur Ed Din, played by the exotically beautiful Franco Merli, (Salo: 120 Days of Sodom.) While in the marketplace, Nur Ed Din encounters the enchanting Zumurrud, a feisty slave girl, being sold at auction. The girl has a spirit of her own and is given permission to choose who her next master shall be. Turning down generous offers from rich old men, she instead selects the young shepherd boy, Nur Ed Din, who is delighted to bring his new slave back to his home. He has not one dinar, but this matters not to Zumurud, who shows the boy the mysteries of eroticism. Of course Zumurud is stolen away after he ignores a prophetic warning from his slave, not to do business with a blue-eyed Christian. A greatly heart-broken Nur Ed Din embarks on an adventure to find his lost love, and this adventure is the centerpiece of this enormous, sweeping film. During his travels he meets many people, who all have their own tales to tell, thus taking the boy on still further adventures, where he encounters genies, giants, Princes, and heart-broken men in search of their lost loves. There are sequences in this film that are so beautiful that they induce chills, such as when Zumurud comes upon the kingdom in the desert, and is greeted by a brigade who name her 'King' of their castle, thinking that she is a man. Or when Nur Ed Din encounters the lion in the desert, and is led by the beast to an enchanted city where his beloved awaits. Featuring a minimal but beautiful score from Ennio Morricone, the predominant sounds are the desert winds, and innocent laughter of children. Rather than employ professional actors, Pasolini wisely uses locals, many who possess the most natural and innocent kind of beauty imaginable. Natural performers who can hardly resist giggling shyly when doing a nude scene. This is a world where sex is portrayed completely without Western guilt, and Pasolini even veers away from the rigid sexual codes of Islam, to bring these magic tales to life, suggesting perhaps that these tales are older even than religion itself. Erotic scenes that come across as playful, some even featuring erect penises, (a rarity in mainstream cinema,) and yet it all still comes off as strangely innocent and utterly pure. If the fantastic tales don't dazzle the viewer, than certainly the cinematography and the beautiful, lush costumes will surely boggle the mind. This is what cinema is really about; a creation of a fantasy world so real, and glorious enough to take one out of reality, and on a great adventure. This must truly have been something to behold on the big screen. "Arabian Nights" was the final film of Pasolini's "Trilogy of Life" collection. A year later he would embark on the first film of his "Trilogy of Death" series. He would not live to see the final editing of his "Salo: 120 Days of Sodom," a film considered by some to be the most offensive and controversial film of all time. Some say that he was murdered because of the contents of that film. But see "Arabian Nights," a true celebration of life and the human spirit.

Truth is not in only one dream but in many dreams. At once treachery in this sun-crashed world. Treachery of a slave who chooses her master. Treachery of a Christian who steals the slave for some Moslem buyer who had been refused by her. Treachery of the desert that forces these people to move around to find water for men and cattle alike. Treachery of love itself that is always at first sight, has little to do with discriminating between boys and girls, women and men. Strangely enough for a long time we believe love is nothing but desire and lust leading to suffering and deception, disappointment. And yet we are to find there is a lot more beyond that simple carnal, though also spiritual, appeal, attraction. There is attachment, an attachment that has to do with fate, a curse, a malediction, happiness. Happiness beyond fate, the curse, the malediction of treachery, vengeance, cruelty. On the track of Zumurud, the stolen slave. And Nordine, her chosen master, is the light of the Lord, the light of that happiness. There is a Song of Song atmosphere here when Nordine does not look after his own vineyard and his Zumurud is stolen again, kidnapped by some other man, a Kurd mind you, after the Christian, and his forty acolytes. The Christian ends up on a cross. The Kurd ends up on a cross. And we are delving into the side-tracks of this main story. There is nothing one can do against the will of God. Then more dramatic stories are going to be told, twisted into and around one another with dramas and more dramas all ordered and commanded by fate no one can evade. The story of the tragic love of Aziz and Aziza destroyed or made impossible by Budur who will end up causing Aziza's death and will castrate Aziz. The story of Aziz and Tadji and the decoration of a pavilion in Queen Dunya's garden, the queen who hates men, and the love that will come out of it. The Stories of the two workers, Shahzaman and Yunan, two dramatic stories of fate that enslaves and victimizes human beings, and their choice to drop everything, sons of Kings that they are, and become mendicants to serve God. A vision of God who is totally absent. Fate is not the decision of God but seems to be some kind of force of its own and the only way to compensate for that necessarily negative fate is to dedicate one's life to God. God is abstract. God has no church, no clergy. God only has these mendicants who suffer for his glory, for his rule. Man is taken between the pagan acceptance of fate and the Godlike attitude that leads to becoming a permanent pilgrim on earth. This power of God is captured in civilizations we understand to be Moslem or Hindu, often at the crossing point between old millennium-long beliefs that edge on superstitions and an abstract notion of God that requires absolute submission. The end of the film hence is completely different because it deals with the second, happy and final meeting between Nordine and Zumulud, between the master and the slave turned king in a love that starts with obedience and ends with passion. In this film Pasolini does not follow a painter, nor a story teller, but a poet, the Arabian poet who speaks of love and the success of love beyond all kinds of difficulties, traps, snares, a love that he embodies in a man and a woman, but that is constantly shown as being ambiguous, limitless, without any boundaries. His vision of the mixing of these two cultures, Semitic Islam and Indo-Aryan Hinduism (note it cannot be Buddhism because of the belief in God) is exhilaratingly fascinating. These Arabian Nights are definitely reflecting that meeting point but here Pasolini makes it a metaphor and a parable of the future of humanity that can only find love, life, a reality in the joining of the various traditions of spirituality that humanity has produced in its divine desire to understand and explain what was a perfect mystery for it, viz. life itself that can only be measured and appreciated when death comes.Dr Jacques COULARDEAU, University Paris Dauphine, University Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne & University Versailles Saint Quentin en Yvelines

Whether or not you like some (or just respond positively to some) of Pier Paolo Pasolini's work, or you don't, will depend on how much one can take of provocative subject matter put forward in an upfront manner. For me, he's a director that can go both ways, be it completely muddled and pretentious (Teorema) or almost boring in its S&M tactics of twisted satire (Salo), or actually dramatically engaging (Mamma Roma), and he's never someone who takes the easy road. Arabian Nights is another one, as part of a 'trilogy' of films adapted from famous, erotically-laced works of stories that have scandalized for centuries (the others the Decameron and Canterbury Nights). Once again, Pasolini has a lot of people in his film that aren't actors, or even real extras- sometimes some people will just pop out, or a bunch of kids will run around, and they're plucked right from the scenery. If authentic, film fans, is what you want, Pasonili gives it, in all of the style of a guy out to shoot a documentary on the people in these settings and gets (pleasantly) sidetracked by a bunch of crazy-tragic stories of love and lust in the desert.As if done in a pre-Pulp Fiction attempt at non-linear storytelling, we get the tale of Zumurrud (Ines Pellegini) and Nur ed din (Franco Merli), one a slave who is bought by the most innocent looking kid in the bunch of bidders. They fall in love, the wise young girl and naive grunt, but they get separated after she gets sold to another man. She escapes, but becomes the unwitting king after she is mistaken for a man. Meanwhile, her young little man is calling after her/him, and getting into his own trouble. Through this framework, we get other stories told of love lost and scrambled; a sad and silly story of a man who's engaged to his cousin, and is thwarted by a mysterious woman who gets his attention, which leads him down a path of semantics (yes, semantics, poetry-style) and sex, leaving his much caring cousin behind. Then there's the man who woos a woman who is under the ownership of a demon, and once their affair is discovered some unexpected things happen via the Demon (Franco Citti, maybe the most bad-ass character in the film despite the surreal-aspect of the showdown). And then one more story, which, hmm....I could go on making descriptions, but then this wouldn't be much of a review of praise of the picture. Suffice to say it's one of Pasolini's strongest directed efforts, where he's surefire in his consistent usage of the hand-held lens, getting his actors to look sincere through dialog that is half ripped-from-the-pages and half with the sensibility of Pasolini as a poet (yes, I went there in the whole 'he's a poet' thing, but he is in a rough-edged and melodramatic timing and flow). He's also going for an interesting combo; neo-realist settings for a good chunk of the picture, set in and around real locations in areas that don't need much production design, and an epic sweep that includes many extras, some special effects at times (and how about that lion!), and extravagant costumes.I also liked- if not loved- how Pasonili dealt with sex and more-so the human body itself. It would probably rightfully get an NC-17 if released today in America, and got an X when released in 1980. The dreaded 'thing' of a man is revealed about as often as a cut-away to a master shot of a building. Everything, in fact, is filmed frankly, without the style that tip-toes around the starkness of two people embraced and naked. But it's also not pornographic either; if anything Pasolini perhaps doesn't direct far enough with the sex, as one body just lays still on top of another. There's a specific intent to dealing with sexuality in this world that respects lust and desire from the original text without making it blatant- only in one big instance, involving the fate of the man from the cousin story (the one with Aziz I think) revels in the horror of sex that was delved tenfold in Salo. Add to this the exquisite score from Ennio Morricone, who enriches any scene his score pops up, as a mandolin strings away and the strings rise with just a hint of the sentimental. Without Morricone, in fact, it might not be as emotional a film, when need be.And lest not forget Arabian Nights can be strangely comical, where Pasolini throws it back at the audience that he knows he's going (rightfully) into the surreal. Like with the story of the Demon and the fate of a man transformed as a chimpanzee, or the vision with the lion, or even the dialog in the pool with the three girls and the man, which is humorous while keeping a tongue-in-cheek. And there's even some good jokes to come out of the obvious step of having Zummurrud as the 'King' when it's clear as day from the Italian dubbing that he's the 'she', so to speak, as it stretches out into a final scene where lovers are united and things are as they should be, however much the director is thumbing his nose at power and sex and the dealings of the heart with organs. Arabian Nights probably couldn't be made today, but could anyone else but Pasolini make it anyway? There's daring in this film, and through the exotic exteriors and sets we see a filmmaker working along like there's nothing else to stop him, for better or worse. This time for the better.