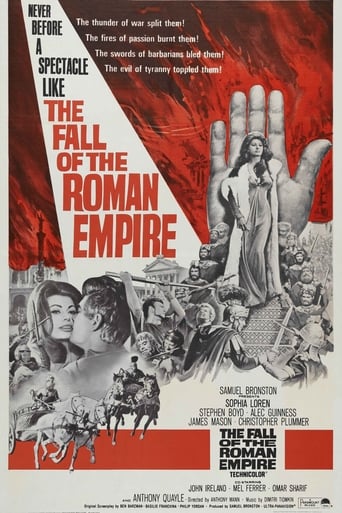

The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

In the year 180 A.D. Germanic tribes are about to invade the Roman empire from the north. In the midst of this crisis ailing emperor Marcus Aurelius has to make a decission about his successor between his son Commodus, who is obsessed by power, and the loyal general Gaius Livius.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Movies like "Southland Tales" are so irredeemably bad that re-watching them could lead directly to insanity and loss of life. Movies like "The Fall of the Roman Empire" can be very enjoyable if one gets properly blazed and mocks them endlessly during a second (or third) viewing, MST3K style.Wow, does this film suck. The cast is the most bizarre collection of mismatched acting styles and accents ever assembled. Techniques like filming Alec Guinness talking to Death in voice-over while wandering around his chambers alone, grimacing, fall flat and become downright painful to watch. By contrast, Ingmar Bergman turned a chess match between Death and Max von Sydow into one of the most brilliant films ever made. Sophia Loren gets the same treatment near the end, but her scene actually becomes so surreal that it borders on hallucination, as she pines for Stephen Boyd in voice-over as she wanders through a giant set crammed with extras from the "Matrix II" Rave in Zion.The plot of "Fall" is rooted solidly in historical fact. It is more or less the same as the plot of Ridley Scott's far superior "Gladiator". Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (Guinness, doing what he can and gracefully making an early exit from this disaster) decides to bequeath the Title of Emperor to General Livius (Boyd), instead of his son, Commodus (Christopher Plummer, giving one of the two performances that I thoroughly enjoyed). Commodus and Livius are best buds, as evidenced by the early scene of the pair simultaneously quaffing wine from upraised wine-skins. This scene is the highlight of the entire movie, and qualifies as Gayest Scene Ever in a mainstream movie made before 1965.Boyd is Boyd, and that ain't good. His individual line readings seem adequate, but the sum total is a hollow, good-looking, thoroughly rehearsed nothing. Sophia Loren as Commodus' sister Lucilla gets tossed into the same pit by the script, and John Ireland is reduced to playing the role of barbarian leader Ballomar as a grunting stereotype wearing a series of hilarious wigs.James Mason as adviser to Aurelius and Greek former slave Timonides acquits himself the best of anyone. His natural acting style of stage-bound histrionics fits the film perfectly, and he is given a few showcase scenes. Like Guinness, he ignores the fact that the script of "Fall" is a cliché-ridden joke, and dutifully builds a character of noble grace and moral strength.The script: UGH. The material is inherently dramatic, as Emperor Aurelius attempts to unite the disparate kingdoms of the Roman Empire into a peaceful confederation. Perhaps the screenwriters were too concerned with the history, and not enough with the dialogue. There is little or no subtext, and very few memorable lines. Plummer plays with the words and makes them his own. Boyd rents them and then abandons them.On paper, this should have been a great flick. It features a cast to rival "Spartacus", and a director who has done very good work elsewhere. I blame the script and the cinematography. The battle scenes are terrible, and the general level of the entire enterprise is about the same as the Steve Reeves/Reg Park Hercules sword and sandal epics of this same period. Indeed, I would rate Mario Bava's "Hercules in the Haunted World" as a much better movie. It is cheese also, but cheese delightfully elevated by being served on a platter of bravura cinematic style, with a main course of beefcake.

The history of Rome begins with it's foundations in Roman myths and fell because it no longer believed in it's own future. In this film, the audience is allowed to witness it's slow decay from the top down. The authority which was Rome's diminished it's capacity to rule and no point more so than it's leader, Commodus (Christopher Plummer). Although the empire retained much of it's prestige, it's true force of arms failed to maintain it's ability to govern. In this movie that power dissolves in General Livius (Stephen Boyd) who despite being offered the seat of power, rejects it. As a result, the audience sees through it's pomp, Majesty and star power to see this movie for what it is, a dismal failure. Despite having Steven Boyd, Alec Guinness, James Mason and Anthony Quayle in it's cast the movie is long on rambling romance and very short on historical drama. Still, there are many good scenes with much appreciated character development. However, in the end, the movie lacks heart but is listed as a Historical Classic. ****

The tutti orchestra blares Elgar. The leather-clad actors declaim with hand outstretched. The cameras pan across the Roman Empire. I yawn. Why, you ask? The beginning is all exposition. Actors usually are hired to show, not tell. Possibly it gets better later on, but as a member of the Baby Boomers, I haven't the nanoseconds to waste on British-accented, slowly developing pseudo-history. Varus, give me back my legions. Then give me back the time I spent watching this. The tutti orchestra blares Elgar. The leather-clad actors declaim with hand outstretched. The cameras pan across the Roman Empire. I yawn. Why, you ask? The beginning is all exposition. Actors usually are hired to show, not tell. Possibly it gets better later on, but as a member of the Baby Boomers, I haven't the nanoseconds to waste on British-accented, slowly developing pseudo-history. Varus, give me back my legions. Then give me back the time I spent watching this.

"The Americans have always depicted the West in extremely romantic terms - with the horse that runs to his master's whistle. They have never treated the West seriously, just as we have never treated ancient Rome seriously. Perhaps the most serious debate on the subject was made by Kubrick in the film "Spartacus"; the other films have always been cardboard fables. It was this superficiality that struck and interested me." – Sergio Leone I wouldn't call Kubrick's "Spartacus" a "serious debate" (Kubrick disowned the film precisely because it lacks complexity), but there is a sense that epics of yesteryear, despite their flaws, nevertheless possess an intelligence which modern epics lack. Think, for example, Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia", Ray's "55 Days in Peking", Houston's "The Man Who Would be King", Kubrick's "Spartacus" and even lesser films like "Viva Zapata", "Ben Hur" and "El Cid". Not to mention those unconventional epics by guys like Visconti, Welles, Leone, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Jancso: "Ran", "2001: A Space Odyssey", "Satyricon", "Chimes at Midnight", "Red and White", "Kagemusha", "The Leopard", "Duck You Sucker" etc.Are there any epics today that match this stuff. "Troy"? "Alexander"? "Kingdom of Heaven"? "Gladiator"? "Lord of the Rings"? "The Last Samurai"? "Avatar"? I don't think so. Despite advances in technology and photography, these films are content to latch onto epically stupid and derivative screenplays.Anthony Mann's "The Fall Of The Roman Empire" is at times a clunky film, but it nevertheless possess a certain substance which modern fare (and imitative stuff like "Gladiator") lacks. The film opens with Emperor Marcus Aurelius and his slave Timonides philosophising about pleasure and pain, Aurelius eventually confessing that he had a childhood anxiety in which he feared that the sun might never rise. This tone – the feeling that all life exists on that thin boundary between day and night, between existence and non-existence – permeates the entire film.We're then introduced to several other characters. There's Lucilla (Sophia Loren), the melancholy daughter of the Emperor, who both idolises her father and hates her mother's constant schemes, plots and infidelities. She also hates the fact that she has to, for political reasons, marry the King of Armenia in order to secure an ally on Rome's eastern front. Much scheming then follows, in which cunning politicians attempt to kill the Emperor and replace him with his more malleable son, Commodus.Commodus is a gladiator loving lug, who indulges in combat and games of war. He knocks skulls and fights barbarians, but is also the friend of Livius, the man whom the Emperor has chosen as his successor. After the Emperor is assassinated, a mild feud thus develops between Livius and Commodus. The politicians want Commodus to take the throne and he eventually does, Livius too kind and humble to stand in his way.Unlike Joaquin Phoenix's version of the same character in Ridley Scott's "Gladiator", Commodus is not an incestuous creep, but an illegitimate child with patricidal fantasies and delusions of grandeur. Narcissistic and tormented, he cuts Rome's ties with all its starving colonies and begins to promote his own imperial grandeur. Rome then becomes a sort of extension of Commodus' inferiority complex, an unconscious manifestation of his own psyche, which inflates and inflates and then comes crashing down, fatalistically crumbling, the illusion no longer supportable.We then launches into several subplots which attempt to describe the historical causes of the empire's collapse: rampant corruption, over expansion, civilisational clashes, inequality, trade problems, the collapse of civic responsibility etc. These issues aren't handled in anything but the most basic ways, but unless one adopts a far more abstract tone, perhaps they can't be handled otherwise.The film then delineates the admittance of a barbarian tribe into the folds of Rome. The barbarians are presented to the senate and arguments made for them to be granted land and citizenship. Livius and Timonides argue that Rome must "change" and be "flexible", that it should cease "conquering" and allow tribes to "freely join" and "trade", whilst Commodus and his cronies argue in favour for continuing Rome's ruthless hegemony.Nevertheless, the barbarians are given their own slice of land, and a sort of relaxed, multicultural Rome begins to form. Commodus detests this, however, and casually orders the massacre of Rome's barbarian citizens. Anthony Mann directed this picture, so of course when the violence comes, its a bit more hard hitting and realistically clumsy than other films of the era.The film ends with Commodus testing his divinity against Livius in a duel. Like the final battle in "Gladiator", they fight to the death, Commodus dying in Livius' arms and Rome's pomp and pageantry along with it.7.5/10 – Though one of the better "sword-and-sandal" epics, this film really highlights the limitations of its genre. Despite its daringly downbeat screenplay (the whole film oozes disillusionment), the fetishizing of the film's huge sets is annoying, the acting is stiff, the production mechanical and the music intrusive. Comparisons to "Spartacus" and "Gladiator" are apt, though "Spartacus" (1960) is far more affecting, going for broad emotions, less politics and more sweep, whilst "Gladiator" is primarily a revenge tale. Incidentally, it was David Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia" (which introduced an aesthetic which suddenly made Hollywood epics feel clunky), the rise of "bloodier epics" ("Zulu" (1964), Italian epics, "Bonnie and Clyde" etc) and the twin box office failures of Mann's "The Fall of the Roman Empire" and Ray's "55 Days at Peking", that pretty much marked the end of these big, Hollywood productions.Worth one viewing. Makes a good companion piece to "Ben Hur", "Spartacus", "55 Days at Peking" and "Lawrence of Arabia". Most of the other epics of the era – "Cleopatra", "The 300 Spartans", "The Vikings", "El Cid", "Robe" etc etc – haven't aged too well.