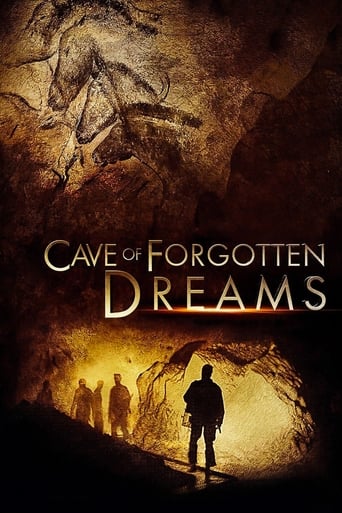

Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010)

Werner Herzog gains exclusive access to film inside the Chauvet caves of Southern France, capturing the oldest known pictorial creations of humankind in their astonishing natural setting.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Documentary filmmaker Werner Herzog gets special access to the Chauvet Cave in southern France that has some of the oldest painted images ever. A landslide sealed up the cave in ancient times and only rediscovered in 1994. It is calculated to date back as much as 32,000 years ago.The cave has an immersive quality about it. I watched it in 2D and can only imagine how 3D would put the audience inside the cave. As always, Herzog is narrating this with his disembodied breathless accented voice. This is more akin to taking a tour of an art gallery while listening to Herzog's commentary. I would have liked more science about the people of the region at the time. Herzog is less concerned about hard science and injects a good amount of poetic ponderings. That's Herzog's style and one can't expect a detailed scientific examination. It does have a compelling moody feel as the shadows almost give a sense of ghostly presences.

. . . (we thought them, therefore they were), one would expect some startling revelations from a film entitled CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS. While it's true that writer\director\narrator Werner Herzog digresses into irradiated albino alligators about 86 minutes into this 90-minute film, this seemingly drug-induced Non Sequitar says more about the state of HIS mind than it does about the FLINTSTONES'. Now, when "Chauvet Cave" was rediscovered 20 years ago in France, it would have been actual news IF the original explorers had found paintings of UFO's, or depictions of AK-47's, or blueprints for pyramids, or perhaps one of Shakepeare's sonnets plastered on its walls. Instead, the interior of this cavern (which had been sealed off by a rock slide for 10,000 years) contained about what you'd expect: crude graffiti scrawled by male chauvinist vandals, mildewed and smeared by 100 centuries of the sort of water damage plaguing homeowners with "wet" basements. Instead of hiring "art" restorers to salvage this as a potential tourist attraction (think Mammoth Cave or Carlsbad Caverns here in the U.S.), the French are planning to clone the hole and its decayed scribblings for a created-from-scratch theme park. Good luck with that! (Herzog SHOULD have made a movie about the dude briefly shown here who proves the tune to the STAR-SPANGLED BANNER was the world's first song: Maybe on the Seventh Day, God said, "Play Ball!")

A large chunk of Werner Herzog's many documentaries focuses on dwarfs, disabled or severely handicapped human beings ("Land of Silence and Darkness", "Handicapped Future" etc). These films tend to be absurdist allegories about a mankind which either triumphs or perishes in the face of what Schopenhauer called Nature's "appalling horror". Then you have Herzog's explicitly religious docs ("God's Angry Man", "Wheel of Time", "Huie's Sermon", "How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck", "Bells From The Deep" etc). These typically focus on different forms of belief (tribal mysticism, mainstream religions, capitalism-as-belief-system etc), ordering systems which, when faith in them collapses, results in the mental breakdowns of Herzog's "mad" protagonists. But for Herzog, belief is itself psychosis and those deemed madmen are but hyper-rational, often with some fantastic insight into reality.Another subset of Herzog's documentaries ("Echoes from a Somber Empire", "Happy People", "Herdsmen of the Sun", "Jag Mandir") tends to delve into different, often primitive cultures. These give way to documentaries like "World Into Music" and "Death for Five Voices", which focus on music, usually Wagner or opera. Then you have Herzog's "flying documentaries" ("The Flying Doctors of East Asia", "Wings of Hope", "Little Dieter Needs To Fly", "The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner" and "The White Diamond"), which again hinge on frail human beings who attempt to lift themselves above a cruel and malevolent Nature. The jungles usually win, of course, leading to calamities, crashes and stark shots of vines strangling steel wreckage.Another subset of Herzog's documentaries focus on either war ("Ballad of a Little Soldier", "Lessons of Darkness") or anticipates outright the apocalyptic end of the world ("Lessons of Darkness", "Wild Blue Yonder", "Encounters at the end of the world"). For Herzog, humanity seems destined to perish and his camera often takes on the perspective of a future, almost alien archaeologist, foraging amongst the wreckage of some long extinct race.Then you have Herzog's explorer documentaries ("Wild Blue Yonder", "White Diamond", "Dark Glow of the Mountains", "Grizzly Man", "Encounters at the End of the World"), which tend to watch as scientists, adventurers or inventors embark on allegorical journeys. Here, nature is often shot so as to resemble either hellish cauldrons or religious cathedrals. Some of Herzog's explorers meet death, some succeed. Typically these men are presented as outcasts who live on the fringes of society, some stable, some unstable, some geniuses, some deeply disturbed.Whilst all of Herzog's documentaries have complex overlaps and can't be as neatly grouped as written above, all chart a broad movement away from German Romanticism, and so the sublime, to absurd, serio-comic tragedies. Or, perhaps more correctly, the majesty, awe and horror of Romanticism is itself that which puts Herzog's characters in an absurd light. Human's are tragic because they are, in Herzog terms, essentially dwarfs. Indeed, the theoretical foundation for the early German Romantics, the Schelegel Brothers' publication of Athenaeum (1798-1800), specifically listed "alienation" and "absurd irony" as the bedrocks of the new intellectual/artistic movement; German Romanticism wasn't just all about grand landscapes and tall trees.Werner Herzog's "Cave of Forgotten Dreams" centres on the Chauvet caves in Southern France, the location of a series of Paleolithic cave paintings which were once thought to be the oldest surviving paintings in the world. The film watches as various scientists (typical of Herzog, they're presented as outcasts, some even former circus workers) investigate the caves, but Herzog is more interested in the ways in which the palaeolithic world is both similar to ours, and forever unknowable. The scientists map and search, but are always alienated from the past, and so desperate to connect with and project upon it. These desires then echo those of our own, ancient cave dwelling ancestors.Much of the film's middle section watches as Herzog draws parallels between cave paintings, 3d films, cinema and the robot camera he uses for several of "Cave's" elaborate shots. Elsewhere Herzog points out that there are 5000 year gaps between some of the paintings. "This duration of time is unimaginable for us today," he says, and later implies that "we are locked in history" whilst "they were not". Our history, our time, is compressed, seemingly moving faster and faster, whilst paleolithic man seems stuck in an infinite moment. The film then launches into a subplot which describes history, not as teleology, but as a complex process with its own causalities. Herzog caps this off with the tale of an albino alligator which stares at its own reflection and which is morphed by climate changes which are themselves wrought by human activity. Humans change, adapt, mutate themselves, but are always looking backwards, back in time perhaps, at their own misconstrued reflections. The film then ends with a prehistoric palm print.Overlong and repeating things Herzog has done before, and better, "Dreams" is a mixed bag. With his doppelganger alligators – like us, the alligator is both contemporary and prehistoric – Herzog aims for the sublime, but can't quite manage. Elsewhere he attempts to imbue his caves with cathedral-like, spiritual qualities, but these moments don't quite come off. For Herzog, the cave is a temple which houses "the beginnings of the modern human soul", a temple which he hopes to fill with subdued passions and profound mystery.What works better is Herzog's dry humour. One scene, for example, features Herzog likening modern man's love for "Baywatch" with ancient sculptures, with their exaggerated hips and breasts. Maybe ancient humans were just like us; a bunch of perverts.7.9/10 - Worth one viewing.

Werner Herzog is given special permission by the French authorities to make a video record of the paintings on the walls of Grotto de Chauvet, the earliest of which were determined to be over 30,000 years old. What he makes is a documentary all right, but one about him and his crew making the documentary about the paintings - this is the key to appreciating this film, which would surely anger viewers expecting more hard info about the paintings and the site.I was enchanted by the labyrinthine passages of the cave and the way the paintings emerged out of the ancient and utter darkness cloaking them, even in 2D. The effect must have been really something in 3D. The sight of the light playing on the paintings with black all around touches some memory so distant and deep that it is irretrievable - yet there nonetheless. This is perhaps the source of the unnerving feeling mentioned by more than one of the experts and crew. I would venture to say that it is, indeed, what the film is really about.Herzog introduces us to and interviews experts involved in the study and preservation of the site, and treats them as veritable subjects alongside the paintings per se. They are a motley bunch, each one what used to be called "a character". I found myself thinking that, from now on, the paintings will depend on them and successors like them for their preservation and interpretation - so why not get to know them? Interviews aside, Herzog does all the talking. True, some of his comments are off the wall, but others are thought- provoking. That is Herzog.Most reviewers were put off or mystified by the ending, but it struck this one as apt. The incongruity of white albino crocodiles thriving in a place where they could never exist naturally dovetails nicely with that of Herzog hauling 21st-century cinematic equipment into a cave to meet people dead 30,000+ years ago. What would the artists have made of these intruders, who may have looked just as strange to them? Which of the two match-ups seems more remote or distant? And the area was ice-age cold then; who could tell how the climate would change 30,000 years from now, and due to what technology - or lack thereof? Thirty- thousand years constitute that much of a chasm. The crocs are there for these sorts of perspective.The spare, even austere, music makes fitting accompaniment. Too bad that Florian Fricke and Popul Vuh, who did many of the soundtracks for early Herzog flicks, are no longer with us - this one would have been right up their alley.Not Herzog's fault that there weren't more paintings to shoot, but the movie does go back over the same ones again and again (the final looks - provided sans narration - are the longest and best). But I, for one, never tired of seeing them. They are inspired in the sense of being spirit-works, and his unique movie shows that Herzog understood this very well.