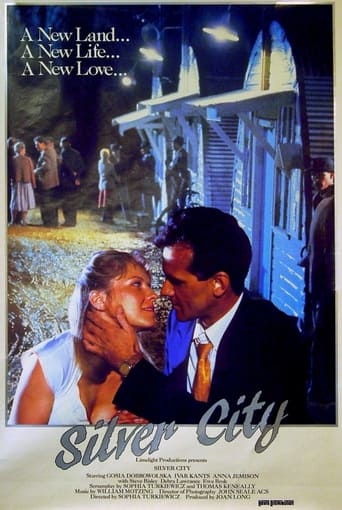

Late Spring (1949)

Noriko is perfectly happy living at home with her widowed father, Shukichi, and has no plans to marry -- that is, until her aunt Masa convinces Shukichi that unless he marries off his 27-year-old daughter soon, she will likely remain alone for the rest of her life. When Noriko resists Masa's matchmaking, Shukichi is forced to deceive his daughter and sacrifice his own happiness to do what he believes is right.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

After having seen and loving Tokyo Story, a film which is widely considered to be not only master Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu's best film, but also one of the greatest films ever made, I was very eager to see more. Many consider Late Spring another of his absolute best works, and I can happily say that it most definitely met my very high expectations. As with Tokyo Story, this a deep, masterfully-executed and penetrating film examining family life in Japan and the societal and generational pressures which shape it.As with Tokyo Story, we enter this tale of father, Shukichi Somiya, and daughter, Noriko Somiya, in the middle. 27-year-old Noriko lives together with her father and they appear to be very close. Naturally, questions begin to arise in the mind of the viewer: where is Noriko's mother and why hasn't she ever married? Ozu does a fantastic job of coaxing these questions out in the film's early stages and gives us hints at what has transpired, but never spoon- feeds us by explicitly explaining the backstory. We learn that Noriko had been seriously ill at one point during a period of war and hardship, but has since recovered. Her mother is a mystery for much of the film, but it slowly becomes clear that she has died and that Shukichi is a widower. With this context, the film examines the father-daughter relationship between Noriko and Shukichi and the pressures on them both to have Noriko finally marry and "leave the nest", so to speak.The strength of this film (and Tokyo Story alike) is how subtly and effectively it tells this story. The screenplay and pacing of the film are phenomenal in slowly and carefully peeling back the layers of the family dynamic. Throughout the film we question the actions and underlying motivations of each of the characters. By the end, the full vision snaps into focus and we are left with a melancholy ending that really sneaks up and packs quite an emotional punch.Let's begin with Noriko. For the length of the movie she is adamantly against marriage, especially re-marriage. As the details of the backstory filter in, her reasoning begins to become clear. Noriko lost her mother which has obviously affected her very much. As a result, she is very close with her father and wary of leaving him behind. Her mother's death obviously must have been very hard for her father as well, and she references the fact that he needs her to take care of him. She feels that she must be there for him because she fears he may be lonely if she leaves and won't be able to cope as a widower. She is also understandably protective of her father – she is afraid to lose him like she did her mother. Thus, she can't bear the thought of him ever remarrying which, in her mind, could potentially jeopardize their relationship. As the film progresses though, pressures on Noriko to get married come from all sides – her aunt, father, and best friend (and ironically, divorcée) all urging her that she must take this long overdue and necessary step. To her, the relationship she has with her father is more than enough and brings her contentment. However, she is made to feel like she is being selfish in staying home with him, especially when it is suggested that he wishes to remarry. Thus, she eventually gives into these pressures and marries at the end of the film, but is clearly devastated and unhappy with her choice.Shukichi can be analyzed in the same way. He seems to be very happy with his daughter home and with the lives they are leading together. It isn't until his sister, Masa, makes the observation that Noriko has gone far too long without marrying, that he begins to question things. He too begins to pressure Noriko that she must marry, and begins to insinuate that he wishes to remarry as well and that she need not worry about taking care of him. Many conversations seem to have taken place between Shukichi and Masa off-screen, as at the end of the movie it is revealed that Shukichi's plans for remarriage were fabricated by both he and Masa in order to influence Noriko in her decision. Shukuchi feigns happiness at Noriko's wedding (as does Noriko quite poorly), but at the end of the film we see him return home to his empty house in a devastating scene where his true distress becomes apparent. In this moment, the movie strikes a powerful note as we realize neither Noriko nor Shukichi wanted for this marriage to happen and neither are happy with the outcome. They were both made to feel selfish by others around them – Shukichi for keeping Noriko home so long with him and Noriko for keeping her father from remarrying. In reality, neither of these two things are true, but the characters are made to believe them through the pressures of their family and friends. Now, they find themselves in places that neither of them wanted or needed, but that society has deemed "correct" for them. It's a poignant and thoughtful tale which is marvelously achieved by the strength of spectacular direction and acting. Setsuko Hara is absolutely radiant and Noriko. She shines in every single scene and has such an effortless quality to her acting that makes her every move feel completely natural. Chishû Ryû as Shukichi is equally brilliant as a caring father who is conflicted between keeping his daughter by his side and shooing her out the door to a more socially acceptable life. And everything of course is tied together by Ozu's absolutely masterful direction which makes for a film that is deep, thought-provoking, and emotionally resonant.

Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is twenty-seven years old and still living with her widowed father (Chishu Ryu). Everybody tries to talk her into marrying, but Noriko wants to stay at home caring for her father.So, this is the first part of the so-called "Noriko trilogy", and I suppose most people would argue that part three is the best. At least, it is the most well-known: "Tokyo Story". But this one had more resonance with me. I loved the cinematography, and I quite enjoyed the Noriko portrayed by Setsuo Hara this time around.The American occupation was also an interesting touch. Ozu could easily have worked around it, making this a purely Japanese film. But he chose to have Coca-Cola signs and other things suggesting an American presence, even if no American is ever seen.

The Japanese people are gentle, nice and polite and plentiful of good feelings. They respect the best values in family and society. Ties between children and parents are very deep. This movie shows that atmosphere in a remarkable way through beautiful and delicate scenes of sociability and intimacy and some dialogues of restrained emotion. A daughter who has already passed the age in which she should have married, lives with her widowed father taking care of him. But her father and her aunt keep pressing her for getting married soon because they think that will be for her own happiness and because socially she should already have done that. Particularly the aunt is engaged in getting her a fiancé. She is however very reluctant on that matter since she feels very happy living with his father and taking care of him. She ends up by yielding to his father's entreaties feeling very sorrowful although she tries to seem cheerful at the idea. Her father even recognizes he would like to have his daughter with him but feels that children must go and leave their families when they become adults. The movie ends on the wedding day (whose ceremony we don't watch not even we ever see the bridegroom since this is not important by the movie's goals). There are two scenes particularly dramatic though in very restrained attitudes. First while the bride is getting dressed in typical Japanese attire for the wedding ceremony not showing any signs of cheerfulness and the last scene when the father comes back home alone and sits down feeling silently his loneliness making us feel deeply the girl's absence where she was so lively before. The movie viewer feels very deeply what goes in their minds and hearts while watching these scenes. The performers know well to communicate their feelings to us without great explosive dramatic scenes. They do a great job at that. This movie was classified recently by a team of British critics as one of the 100 best movies ever made.

As in the films of Bresson, to Ozu the purity of style always coincides with an uncompromising moral perspective. He never lets his characters nor his audience get away from a profound dilemma with an easy answer. Thus, Ozu's films are always veritably life-enhancing, exhaustive, in the word's most definitive meaning. In "Late Spring" Ozu's mature, extremely laconic style is at its most developed before his subsequent films in which he went to define it even further. The movement of the camera is precisely considered; it is often positioned approximately one meter from the ground, and often left to explore the space long after the action has taken place. The lingering narrative of "Late Spring" fits very well for Ozu's understated poetry which encapsulates his whole vision of humanity and the world. The impressionistic picking of details in the aesthetics triggers associations to various thematic contrasts, such as infinity and insularity, but in addition to such stylization the film bears a striking resemblance to Italian neo-realism with its documentary-like observations and dark visual tones. The quiet emptiness of the beginning shots -- the essence of Ozu's poetics -- and their atmosphere remain as an echo in all of the scenes of "Late Spring" where there are no superfluous images. In his unique style Ozu has set the rhythmic pace for the junctions of the scenes with brief shots of nature that seem to express the transience of life; the importance of moments; and their absolute beauty. Once again Ozu deals with the theme of collision of generations as people must ponder responsibility and freedom with regards to tradition and family. Not surprisingly, the film has no black and white solutions to offer. Ozu's honest pessimism, his Chekhovian wisdom of life; and Buddhist acceptance merge together in the beauty of his aesthetics. At its heart, "Late Spring" is one of his most profound meditations on happiness, its pursuit, limits, nature and impossibility.When it comes to the story or narrative of "Late Spring," it is vital to discuss inner drama. For this is truly a film about characters who cannot express themselves, their true desires and wishes. It is to them whom Ozu gives his silent and tender interpretation, understanding their deepest experience of existence. In this sense, "Late Spring" can be seen as a universal tragedy of the difficulty of expressing oneself; of revealing one's innermost emotions and dreams.