Early Summer (1972)

A 28-year-old single woman is pressured to marry.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Calm and serene with a thin plot, "Early Summer" looks at a family and the changes it undergoes as a result of one of its members deciding whether or not to marry. The movie is set in early 1950′s Japan which was under American occupation and associated social influences at the time. Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is a clerk in her late twenties under pressure from her family at home to find a suitable husband. Even her boss at work jokingly suggests she should meet an old school friend of his to see if they're a good match for each other. Noriko sweetly bats off all these hints that she's nearing her meat-market use-by date and should be settling down to obedient, passive housewifely duties. Her social set divides into singleton and married-women camps arguing the pros and cons of single-hood and supposed wedded bliss so she's well aware of what she'd be walking into if she got that gold band on her finger. Interestingly, the one person who doesn't hassle Noriko about getting married is her sister-in-law who's harried by two small sons spoilt by their grandparents.The visual style of "Early Summer" is highly commendable: the camera positions place considerable physical space between us viewers and the characters. The cameras themselves are set at table height or at the level Japanese people traditionally kneel down to eat at low tables at home. Deep focus fixed-camera shots are used so people are often filmed in the background having conversations or doing things while framed by doorways, furniture and other interior fixtures. If the camera moves at all, it is to track people coming towards it or going away from it, or to pan slowly across the screen over a nature scene. The effect is to give "Easy Summer" a static, almost stage-like quality and viewers will feel very much like voyeurs peeking into people's private business. The very minimal acting places psychological distance between us and the characters. By forcing such physical and psychological distance, viewers observe the story as it develops and don't get deeply involved; this helps to reinforce the film's theme about how change affects families and the relationships within them for better and for worse. We shouldn't get upset if people suffer as this may be a short-term effect of the change and there may be long-term benefits; equally a short-term benefit may lead to adverse long-term effects."Early Summer" observes the pressure Noriko is under to conform to tradition and expectations amid fluid social, political and economic conditions, and the frustrations and distress that she experiences when social custom clashes with changing reality. At first she's unwilling to surrender her freedom, financial independence and closeness to her relatives but after continued pressure from family and friends alike, she suddenly decides to marry a widower with a child. The irony of her decision is that her relatives disapprove of the idea of a proved family man as husband over a man aged 40 years who's never married and might not be family-man material; and Noriko's impending marriage means her income will be lost to her family so her brother and his brood must move to a smaller house in Tokyo and the parents must live in the country. The hypocrisy and shallowness inherent in forcing a woman to marry purely to preserve social standing and harmony without thought for practical consequences become apparent.The acting is so sparing in its expression as to seem stereotyped: most of the women are chirpy and giggle a lot; the men stick to one mode of expression throughout the film so Noriko's boss is usually jovial and her dad and various other aged people usually act bemused at the pace of modern life. Hara does a good job within the limits set by director Ozu at portraying a woman who hides her anger, sorrow and despair behind a cheery and upbeat façade.Scenes of restless nature (beach scenes of rolling waves near the beginning and the end of the film, a scene at the end of rippling wheat ready for harvest) and of the Tokyo cityscape reflect the ongoing and impassive nature of change. The small children with their obsession with model train sets and demand for lollies and gifts are the focus of a small subplot emphasising generational differences which come with social and cultural change.Slow and reserved it may be but "Early Summer" isn't at all stodgy; it just glides by, inviting neither scorn nor sympathy for its characters. The film does suffer from not being in colour which would enhance Ozu's style of filming by adding depth to deep focus shots. Mood and atmosphere might be improved with appropriate colour choices in the interior and costume design. One aspect of "Early Summer" that some viewers might find troubling is the fatalistic attitude expressed by Noriko's parents in their new digs in the country when they kid themselves that they're happy and shouldn't ask for more in life. Their facial expressions suggest their confusion, unhappiness and feeling of being tricked or trapped in some way at the way things have turned out as a result of their daughter bowing to convention and tradition. This moment captures very well the bewilderment of a society caught up in political, economic and social changes not always of its own making.

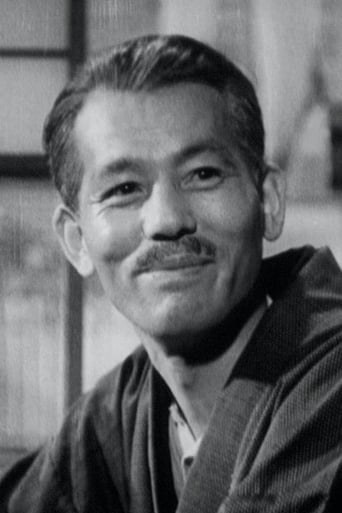

As other readers already commented, Early Summer (or Bakushu, made in 1951) is easy to confuse with another movie by Ozu made during the same period: Late Spring (1949). Aside from the references to the seasons in the title, both deal with the "problem" of the Setsuko Hara character (she of the ever wonderful smile) still being unmarried in her late twenties. (Ironically, in real life, Setsuko Hara never married and become something of a recluse in later years). Curiously, Chishu Ryu, who played her father in Late Spring, plays her brother in Early Summer. The slight plot deals with the pressure and machinations made by the extended family to find a suitable husband for her. When she finally does find a husband, however, is not the one they were expecting. Her new husband would have to move to another city for job reasons soon, and that means the splintering of her family: without her contribution to the rent (she works as a tourist guide, as so many young unmarried women in Japanese movies of the 1950s), the family will not be able to afford living in the same house. Her actions would eventually mean the return of her parents to the countryside. That means the movie ends in a bittersweet note: on the one side, Hara has attained some degree of freedom in choosing her own spouse, but for her family, this freedom would end up hurting them financially and emotionally.

Having just enjoyed the quiet brilliance of Yasujiro Ozu's "Tokyo Monogatari (Tokyo Story)" for the first time last week, I was immediately drawn to another Ozu film released by the Criterion Collection last year, 1951's "Bakushû (Early Summer)". Both movies are part of his classic Noriko trilogy which uses many of the same actors playing characters with the same names but in different roles. Consequently, the great Setsuko Hara portrays a young woman named Noriko in both movies, but this time, she is the liberated daughter (rather than the forlorn daughter-in-law) and also the focal point of the story (rather than the aged parents in "Tokyo Story").The musical chairs continue with Chishu Ryu playing his real age as Noriko's strong-willed brother Koichi (rather than the resigned grandfather) and Haruko Sugimura playing older as neighbor Tomi, the mother of Noriko's prospective fiancée (versus the conniving daughter Shige). Chieko Higashiyama still plays the grandmother, but her name is not Tomi but Shige, and her husband Shukishi is portrayed by Ichirô Sugai. It's only confusing if you are looking for some kind of plot continuity between the films, but Ozu is primarily interested in reinforcing similar themes of the evolving family unit in post-WWII Japan. This time, he does it in a more comic, sometimes even ribald fashion, and while it doesn't resonate quite as deeply as "Tokyo Story", "Early Summer" is full of Ozu's shrewd observations and insights that make it emotionally affecting, especially as the story takes a surprise turn toward the end.The story here centers on the Mamiya family, who are trying to find a suitable husband for 28-year old single daughter Noriko. As typical in Japanese culture, several generations live together under one roof, and a frequent subject of conversation is Noriko's lack of a husband. However, she is a member of the new postwar breed of Japanese women. She dresses almost exclusively in Western clothes and holds down an administrative position in an office in the heart of Tokyo. In spirit, Noriko bears a strong resemblance to Elizabeth Bennett in Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice", a point raised by film historian Donald Richie on his informative commentary. She loves to go to dinner with her girlfriends. Of the four friends, two are married and two are unmarried. In a particularly amusing scene, the four have a spirited debate about the pros and cons of married life versus single life.Noriko is happy with her life as it is and doesn't seem to be too concerned with changing it anytime soon. Nonetheless, the family attempts to fix Noriko up with a successful, 40-year old business associate of her boss. Although polite about the matchmaking effort, she becomes more interested in her neighbor, an old classmate now widowed and left alone with a small daughter and his mother. Noriko prefers that her potential husband is an old friend and that they will slip into their new romantic relationship more easily than two complete strangers. The bigger problem, though, is that she makes her decision without consulting with her family and that's where the familial conflict arises.Hara continues to be a revelation to me, a beautiful, charismatic actress who radiates goodness and a sense of cunning mischief that is entrancing. The supporting performances are excellent with Sugimura again a standout in a surprising turn as the mother grateful to Noriko for her decision to marry her son Kenkichi. Kuniko Miyake has a bigger, more dimensional role here than in "Tokyo Story", playing yet again the brother's wife Fumiko. She and Hara have a particularly lovely scene on the beach at the end of the film, and the two have a pretty funny scene where they hide their clandestine cake slices from the somnambulant child.Chikage Awashima portrays Noriko's best friend Aya with feisty charm, goading Noriko to see the man she passed up, impersonating a country bumpkin to preview Noriko's new married life and trading innuendo-heavy barbs with Noriko's politically incorrect boss. This latter interchange is surprisingly adult for 1951, as they even joke that Noriko may be a lesbian for waiting so long to get married. The children play more prominent roles here, and Ozu really plays up their bratty insubordination as they hurl inappropriate epithets when they don't get their way, though their running away from home is the catalyst for Noriko to become attracted to Kenkichi.Yuuharu Atsuta provides the beautiful cinematography, which is gratefully captured in a fairly pristine print of the film, though I have to believe Ozu is the one most responsible for the simple yet powerful scene compositions. His now familiar low-to-the ground camera angles are used consistently in the film to replicate the perspective of someone sitting on a tatami mat. Lighter and more loosely structured than "Tokyo Story", "Early Summer" is essential viewing for Ozu aficionados and anyone interested in post-WWII Japanese society. Along with Richie's thorough commentary, the DVD package also includes a 47-minute documentary, "Ozu's Films From Behind the Scenes", which includes a table discussion with Ozu's longtime cameraman Takashi Kawamata, his sound and editing assistant Kojiro Suematsu and producer Shizuo Yamanouchi who produced six Ozu films.

I did not know much about Yasujiro Ozu's films prior to seeing Early Summer. I knew he was as big an influence in the West as Akira Kurosawa. It is not difficult to understand Kurosawa's influence since his films were largely influenced by John Ford and his stories were occasionally based on Shakespeare. Ozu, seems to take a quiet and simple approach to the cinematic experience."Early Summer" is about a time when families extend and break apart. We are introduced to the Mamiya family, a typical family of 1950's post war Japan, who we see going about their daily life routines. The protagonist is the daughter Noriko, a 28 year old girl whose parents believe is ready to get married. One day, Noriko is recommended a man Takako, who is an associate of her boss. Noriko considers the offer but does not spark much interest. Her parents try to encourage her daughter to marry this man but after learning that Takako is much older, Noriko becomes even more reluctant. One day, their close neighbor Kenkichi, has been offered a job outside of Tokyo and has decided to leave. It is Kenkichi who Noriko suddenly decides to marry. The Mamiya family becomes upset because Kenkichi is not only moving away from home but he is also a widower with a child. The parents soon realize that they will have to accept and nothing will be the same again. The story has a somewhat similar structure to a documentary in that we sometimes feel as though we are witnessing real life as it happens. Much of what occurs throughout the film is not directly connected to the story. There is no surprise or ironic conclusion. Everything seems inevitable and there is no major surprises or conclusions. "Early Summer" helps us think about the essence of selfishness in the Japanese nuclear family. It is uncommon for Japanese families to leave the family because independence is looked down upon. At the same time, it is inevitable that things change for better or for worse. There is a wonderful scene with the grandparents contemplating on Noriko and their lives. "Things couldn't be better" says the grandfather. "Well they could" says the grandmother. The grandfather replies,"please, we must not expect too much from life" This seems to be an important awareness of the film and one that exists between the Mamiya family. Noriko accepts who she's in love with not because she seeked him out but because it occurred when she least expected. She tries to read into her future and accepts that marriage will be difficult. There is another wonderful moment after she has accepted Kenkichi's mother to marry her son, she is seen walking home and passes by her soon to be husband. Their exchange is very subtle and brief and yet we know they are going to spend the rest of their lives together. This scene is presented in an ironic way that helps us to pay close attention to the mundaneness of our lives. These are the moments that help us see the world in better light. Ozu has a great eye for timing, atmosphere and above all, humor. There is nothing pretentious about this film. It is an examination of family unity and the passing transition of marriage.