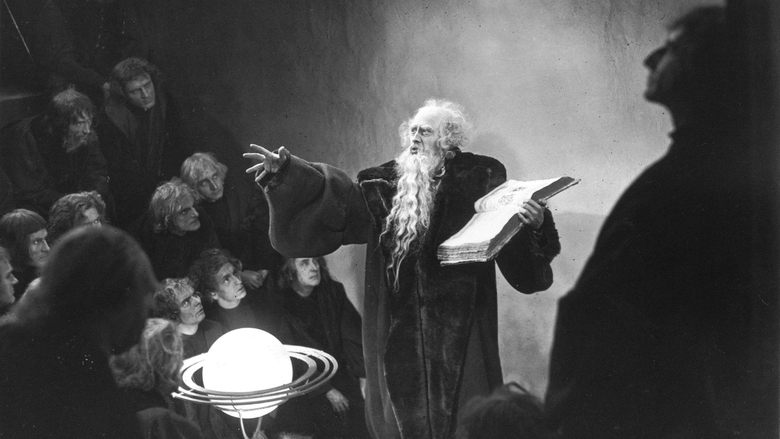

Faust (1926)

God and Satan war over earth; to settle things, they wager on the soul of Faust, a learned and prayerful alchemist.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Two great European myths emerged from the early modern period, despite its being a time of print culture: that of the great seducer, Don Juan, and that of Faust, the frustrated intellectual who strikes a pact with Hell. These are myths in the sense that they are the exclusive property of no individual author, but belong in common to the whole culture (as Murnau's subtitle, calling this a "Volkssage," reminds us); and as such they are susceptible to wide variations in the telling. The tale of Faust began humbly enough (by literary standards) in the anonymous German *Faustbuch*, which, quickly translated into English, soon became the basis for one of Kit Marlowe's greatest plays. After that brief emergence into high culture it went low-brow again, becoming a staple of German puppet theater, and wall-paintings in beer-cellars like Auerbach's in Leipzig. Lessing saw its possibilities, and Goethe (who had drunk at Auerbach's as a student) realized them in the greatest work of German literature--on which he lavished much of a very long life. Goethe's work inspired Romantic artists including not only Byron (as in "Manfred") but also opera composers ranging from Ludwig Spohr to Hector Berlioz, Charles Gounod, and Arrigo Boito.Murnau's splendid (and now splendidly restored) silent film takes its cues primarily from the Goethe and Gounod versions, but goes its own way too, as is quite right. Goethe, after all, was writing a "closet drama," that is, a play meant to be read rather than performed and seen in a theater (though the first of its two parts is widely considered stage-able); but Murnau was creating a photo-play in which any words had to be in the form of disruptive title screens; and so the verbal component, which for Goethe was the whole, had in film to be kept to a bare minimum. This underlies and justifies many of Murnau's departures from Goethe's splendid precedent--departures that offended me when I first saw this film many years ago, in a far inferior version, but that I now see the reason and justification for. In any case, those of us who are familiar with Goethe's *Faust* (as Germans tend to be) are seeing a rather different movie here from the one that others see--for better and/or for worse.From Goethe (himself borrowing from *Job*) this film takes the notion of a background wager between Heaven and Hell, here providing that if Faust falls, spiritually, Hell gets to rule the whole earth. This being a film from Germany a quarter of the way through the twentieth century (which Al Pacino, as the Devil in *Devil's Advocate,* memorably characterizes as "all mine"), the terms of the wager provide no sure clue which side will win it. The *Faustbuch,* Marlowe, and Berlioz all consign Faust to Hell at the end; Goethe, Gounod, and Boito all redeem him. What will this film do? Find out! The emphasis on "youth" (as the main desideratum for which Faust bargains with the devil), and the disproportionate (relative to Goethe) emphasis on the love story with Gretchen, both show influence from the Gounod opera. An example of Murnau's departing from both precedents is having Mephisto himself commit a murder that in both Goethe and Gounod he manipulates Faust into committing; but the underlying idea, that Mephisto is prepping Faust for Hell and damnation by leading him to despair of salvation, is rightly maintained. Also, where Goethe has Faust recall a plague when his and his father's medical science utterly failed to help people, Murnau makes that plague present, and Faust's inability to help is the immediate cause of his spiritual desperation. A maiden who appeals in vain to the aged Faust for medical help (for her mother) is a near look-alike to Gretchen, a nice touch.Jannings is a splendidly louche, unhandsome devil (here named "Mephisto," the only name bestowed upon this character in actual dialog in Goethe, though speech prefixes give "Mephistopheles"). His tactics are ingeniously contrived to keep outright magic to a minimum, relying on spiritual cunning instead. Camilla Horn seems too much the stock silent heroine early on, but grows mightily as Gretchen suffers. Gösta Ekman as the title character is perhaps weaker in his young guise, but his ability (with great help from makeup) to represent both old Faust and young is breathtaking.Makeup in general is too stagy for the frequent sharply focused closeups, so that we see it AS makeup. For special effects, shots of the apocalyptic horsemen, and shots of Mephisto and Faust on the back of some rough beast supposedly carrying them through the sky, may induce some cringes; but otherwise the quality is astonishingly high for the period, with model sets exquisitely designed, built, dressed, and photographed. The soundtrack of the 1997 restored version features only one each of cello, trumpet, violin, clarinet, and piano, and so sounds a bit thin, and also rather repetitious, but it is enlivened by intelligent quotations from both Gounod's opera and Schubert's setting (from Goethe) of "Gretchen am Spinnrade."

The demon Mephisto (Emil Jannings) wagers with God that he can corrupt a mortal man's soul. Apparently, director F.W. Murnau wanted Lillian Gish to play Gretchen, but she insisted that the film be shot by her favorite cinematographer, Charles Rosher. Murnau instead cast newcomer Camilla Horn, whom he had met on the set of "Tartuffe" (1925), where she was a double for Lil Dagover. Now, I would much rather have seen Gish or Dagover in this role, but Horn holds her own and makes a mark on German film history.The imagery is what sells this film: from the beginning with the creepy four horsemen, to Mephisto unleashing the plague, and beyond. The story is a classic (I mean, this is Goethe we are talking about) but it is even more classic because of the way Murnau was able to present it in 1926, a time when special effects were in their infancy.The only unfortunate this is that Karl Freund had to drop out, as this would have been yet one more classic film to put on his resume.

The special effects in F.W Murnau's expressionism masterpiece Faust - Eine deutsche Volkssage (Faust) are just astonishing. I was really surprised when I saw the flying sequence with the weird bird creatures and inventive camera angles, it looks so modern compared to other films of the time and even many films made after it. Its also very creepy at times(mainly in the beginning) and tells a classic tragic story of love and the battle between good and evil(even though it doesn't at all times make a clear distinction between the two).(Slight spoilers ahead) The moral dilemma is probably the greatest when Faust says he'll "help the people in Satan's name" and as he is trying to save a child from the plague he is stopped by the crucifix the child is holding and then is almost stoned to death by the townspeople (who he is trying to help in the first place) because he can't bare to look at the cross and is in league with the devil.Acting in Faust is great same with cinematography and the story is just so captivating. Highly recommended for fans of silent horror,silent cinema and German expressionism.

F.W. Murnau's "Faust. Eine deutsche Volkssage" (1926) is based on Goethe's "Faust I", the movie takes as direct text basis a libretto written by Hans Kyser which differs remarkably from Goethe's dramatic play. For example, Kyser motivates the physician Dr. Faustus's pact with Mephistopheles through his mercy for the victims of the plague, while in Goethe's work, the basic motivation of Dr. Faustus is the enlargement of his scientific knowledge. It is thus interesting to see that Mephisto or the devil represents the darkness from which all the additional knowledge seems to come which cannot be reached by Dr. Faustus in the world of the light in which God reigns. It is this negativity of the darkness as opposed to the positivity of the light that parallels the dichotomy of Good and Evil as well as the dichotomy of Volition and Cognition. So, Dr. Faustus' fundamental metaphysical attempt is to control the dark empire of the will that cannot be controlled by traditional science settled in the bright empire of the thought. It even seems that negativity stands for reflection, and reflection comes from the darkness that in the same time represents Evil. Moreover, since the Being is defined by the positivity of light, cognition and Good, the negativity of darkness, reflection and will must be defined by the Nothing, since in classical logic there is no third instance between them.Therefore, we may see Murnau's "Faust" not only as a movie dealing with the ethic categories of Good and Evil, but also with the metaphysical categories of Being and Nothing. Dr. Faustus, signing his league with the devil, opens the curtain that separates the Here and the Beyond, he transgresses a border of no return. When Mephisto promises Dr. Faustus that he may enter the contract "only for one day", it is quite clear why Mephisto can always turn around the hour-glass in order to prolong the lasting of the league: Eternity cannot be split; if you take out a piece of Eternity there will remain still Eternity. Since Dr. Faustus is a human being and hence does not participate in Eternity, it follows that he will not be able to stand in this never-land between the contextures of Good and Evil, of Darkness and Light, of Cognition and Volition, of Being and Nothing, of Here and Beyond. His intermediary position is shown by Murnau in the often overlooked scene where Dr. Faustus, who had meanwhile turned by aid of the devil into a young man, is charming a young Indian princess while a pendulum above them is vacillating between light and darkness.Murnau must have had in his mind a poly-contextural world when he shows us Mephisto holding the mirror in which the picture of the old Dr. Faustus appears, although he had already turned him into a youth. Not only does the mirror not reflect Mephisto who is holding it, but it reflects the picture of somebody else and even has a memory of the former state of this person. This phenomenon does not fit together at all with traditional logic in which the mirror can be seen as the operator who turns position into negation, falseness into truth and thus operates like a light-switch that, clicked on twice, leads back to the original state, i.e. from light via darkness back to light or from darkness via light back to darkness.Now, at the end of his life, Dr. Faustus stays in the borderland between light and darkness that cannot be shown at the hand of a light-switch, since this never stops in an intermediary position between light and darkness. Because the light-switch serves as a model for classical logic, we have to deal in Murnau's "Faust" with trans-classical logic and thus with a world in which there are not only the dichotomic contextures Here and Beyond, Being and Nothing, Cognition and Volition, but a never-land as a third instance between them, and thus we read on one of Gerhart Hauptmann's titles the phrase "At the Gates of Darkness", the gates representing this third instance between the dichotomic contextures of classical logic.When we read on another title toward the end of the movie "Death sets all men free", it is clear, that Dr. Faustus, after having entered the border-land between the Here and the Beyond by signing his pact with Mephisto, is on a trip that can only end in the Darkness, the Nothing and thus his Death. Once somebody has crossed the borderline between the contextures, he is on a trip of no-return. But such an end would fit into classical logic and thus not fit together with all the hints Murnau gives us toward polycontexturality. Murnau therefore needs a third instance between the contextures by which Dr. Faustus can be rescued from Death representing Evil in two-valued classical logic, both belonging to the contexture of the Nothing. Since Evil can only be neutralized by Good, this third instance must come from Good in order to finish Dr. Faustus's life not in the darkness of Evil, but in the light of Good, and this instance is his love to Gretchen. But in order to achieve that, Murnau needs another trick that does not fit into classical logic: Since Dr. Faustus has meanwhile turned back into the old man he was at the beginning of the movie, Gretchen must remember the alter ego of Dr. Faustus as a youngster, and Murnau shows this by fading over the pictures of the two alter egos of Dr. Faustus. In other words: Murnau achieves to establish Love as a third instance between the contextures of Good and Evil by doubling Dr. Faustus' individuality using paradoxically the dichotomic means of classical logic. When Dr. Faustus and Gretchens die together at the stake, they have finished their trip in to the light that leads them out of darkness: "Death sets all men free".