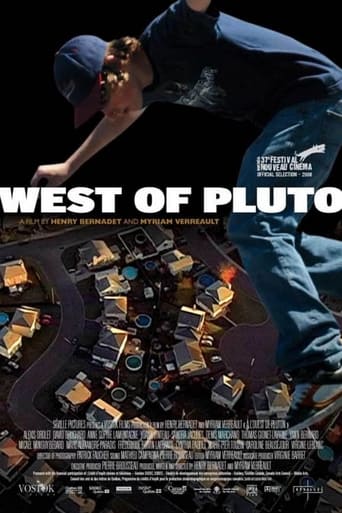

Pigsty (1969)

Two dramatic stories. In an undetermined past, a young cannibal (who killed his own father) is condemned to be torn to pieces by some wild beasts. In the second story, Julian, the young son of a post-war German industrialist, is on the way to lie down with his farm's pigs, because he doesn't like human relationships.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

"Porcile" is fine if you have the patience and the will to endure its lost and bizarre images or its strange deviate messages. Reactions about it will be mixed, rarely reaching some certainty, but the one that's definitely is that this is one of weakest films ever directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. It's too pretentious, looks like his own version of Godard's "Week End" but less brutal, less gross yet more confusing in its speech. Both films deal with world going to its ending, total destruction all around and all hope lost, and Socialism seems to be the good alternative for our better sake. The directors of both films mixed their political speech in the middle of the controversial and shocking images.Two stories form the whole: 1) one young man (Pierre Clementi) who has killed his parents and ate their flesh walks around from village to village after being sentenced to perish in the vast desert. The only thing he'll be able to do is to kill whoever show up on his way and then eat them too. That's the story of the young cannibal, marvelously presented without words (he only has one spoken line repeated towards the ending). Beautiful cinematography, scary and thrilling sequences in it. 2) this story, very talky and quite messy brings Jean-Pierre Léaud (who was also in "Week End") as the son of an German industrialist who can't connect with people, preferring the company of the pigs ("Porcile" translates to "Pigsty"). He tries some involvement with a girl (Anne Wiazemsky) but with no luck. And there's his father (Alberto Lionello) business deals with a former Nazi of name Herdhitze (Ugo Tognazzi) also businessman but a rival of his, who hasn't aged through the war years after successful plastic surgeries. Foggy speeches about life, politics, mankind are dissolved into this other story and it's very hard to form a whole idea. They're apart in time but what they have in common? World going to an end, the destruction and corruption of societies, with everything out of control. Those are recurring themes in Pasolini works ("Teorema", "Salò" just to quote a few) but in here there isn't much going on to make them feel useful for all of us. This is a case that might look better in a book/screenplay/written work than filmed. The experience is distractive, confusing, rarely captivating even with the two known main stars, who had their voices strangely dubbed in Italian (I have my doubts about Pierre, I believe he really learned his lines in the other language). I like the film even though I can't connect with much of what's shown in it. The cannibal story is interesting; the one about the industrialist's son isn't all that much. The final result is chaos. Chaos in this problematic world that doesn't seem to get better. Well, at least in those predictions the master wasn't all that wrong. Enjoyable but unsustainable for more than one view. 6/10

This movie is a testament to the power of poetry and its capacity to dwarf the medium of cinema. Pasolini merges the rites of passage towards 'bildung', {German concept for the development of civilizing Culture}, using five separate themes; - the immature rapport between a wealthy, young bourgeois couple, {named Julian and Ida}, the dilemma of Julian's parents, who desire the union, {it would be materially beneficial}, and the contrasting styles of two German plutocrats, - all this Pasolini combines and contrasts with the historical Italian vagabond life of a countryside bandit , circa the early 1500's, armed with a musket, roving the barren hilly escarpment in the Pompeian district and preying on unarmed, vulnerable Christian pilgrims on their way to Rome.Julian and Ida play at being in love - but their inexperience leads them to compromise reality with their love of words. Julian is a spoilt young man who has been infantilized by his doting mother, who in her ensuing dialogue with Ida reveals herself to be totally blind to her son's character, believing instead that Julian has all the laudable attributes of a good German. The narrative flow concerning this German family, shot as an interior with much opulence, antique furniture and Renaissance paintings, in enormous palatial rooms, which as the story moves forward, is intercut with desolate scenic waste as the vagabond displays primitive savagery, in killing, dismembering and cannibalizing his victims. These scenes are in a landscape that is evocatively lyrical and empty of civilization {that is apart from the hymns which are beautifully chanted by the pilgrims on their way to destruction}.In a parody of Godard and Truffaut, it soon becomes obvious that the love of the two 'pretty young things' is doomed to fail {as the barrier that they set up between each other with meaningless words becomes insurmountable}. The movie now shifts into its essential focus. The two plutocrats, the one, being Julian's father Herr Klotz, a German word for 'idiot' or blockhead, and the other, Herr Herdhitze, meaning 'hot fire' {possibly a reference to the exterminating ovens}, square up as two contrasting sides of the German psyche. Klotz, a humanist, is a cultivated man with a sense of cynicism and an appreciation of the accurate satirical art works of George Grosz - he sees himself depicted by Grosz sitting in a café with a sexy young secretary on his lap, cigar in his mouth and a piggish face - he also refers to Brecht's championship of the workers. Herdhitze, a technocrat, on the other hand, refers to himself as a man of science, who despises individuality, and wants to convert all the impoverished farmers to technicians - he has no soul at all.The two men face off with the core of the German problem - their love of the meat of the pig. Their dialogue .... Klotz - 'the Germans love their sausage' to which Herdhitze replies 'shit' Klotz 'but they do defecate a lot'. The ironic impasse between the two Nazis is whether Jews are pigs or not - with the added Surreal contradiction of, if the Jews are pigs why do the Germans love their pork. and why do they grunt like pigs?The year is 1959, in the German quest for an economic miracle, questions of Jews and culture are easily overcome, and the two plutocrats combine forces, in the pursuit of their worship of material wealth. Meanwhile Julian has resolved his confusion, and sacrifices himself to the totem of the pig, by going to the German Temple - the Pigsty - and there offers himself as an anointed meal to the pigsPasolini has wrought a great work of Art that might have been an Epic Poem or a great novel or a great Painting like Picasso's 'Guernica' or Goya's 'Atrocities of War'. He certainly has no sympathy whatsoever for the Nazi German and his god 'The Pig'. This is a difficult movie to digest, but it's rationale is crystal clear. If you are interested in the History of the Intellect, then this movie is unmissable.

Bsesides his final work "Salo", the "Porcile" is Pier Paolo Pasolini's most abstract, most hermetic and thus most and also most controversially discussed film. In a famous German reference work of film, this movie is interpreted in the following way: both cannibalism and sodomy be "symbols" of Pasolini's homosexuality. I have seldom read something more stupid and primitive. Moreover, in all reference commentaries that I have seen so far, the interpreters seem to be sure that "Pigsty" consists of two independent parts.In one of the two parallel told stories, a cannibal who seems to live in a paleolithic world, is condemned to be mangled by dogs. In the other parallel told story which plays in a German (?) castle, some negotiations of leading fascists are told. Here we see the ultimate predecessor motives of Salo. There is also a son, Julian, bourgeois like his father, who meets Ida, a liberal girl, and it seems that they cannot come together. The water that separates them looks like the border between the Here and the Beyond and not like a swimming pool embedded in a piece of park. Even when they try to walk towards one another, the never succeed in reaching a meeting point on one of the borders. Julian, however, prefers to enjoy his sexual contacts in the pigsty that belongs to the park of the castle, with the pigs that finally eat him up. The two parallel told stories have in common, as Pasolini himself said, that "bourgeoisy eats up his children". This may be true - since the time of evolution between the paleolithic and post-war fascistoid Italy just made the short step from cannibalism to sodomy.

I honestly admit that this film was not easy for me. But I believe that the only intention of director was to express language more beautiful and therefore with more power and suggestion. And I think this is why Pasolini is Pasolini and not Spielberg. There are three important pillars in this society that converts, under Pasolini's view, our existence in corruption: capitalism, Burgess and catholic religion. Somebody has already talked about the first (Burgess is a consequence) but I didn't heard anything yet of catholic religion. The second history (dream of the first?) ends up by dogs eating bodies of those men who first were forced to kiss the cross. Julian died devoured by pigs. Both had follow opposite ways of compromise but both died because of the beasts. What I understand is that even if Julian had followed second history (...I killed my father, I ate human flesh...) cannibalism of these powers would have defeated him. The role of the priests in second history is just to denounce the intolerance, hypocrisy and aim of power and control of Catholic religion.