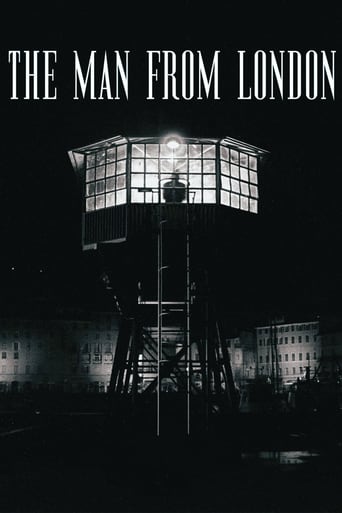

The Man from London (2007)

A switchman at a seaside railway witnesses a murder but does not report it after he finds a suitcase full of money at the scene of the crime.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

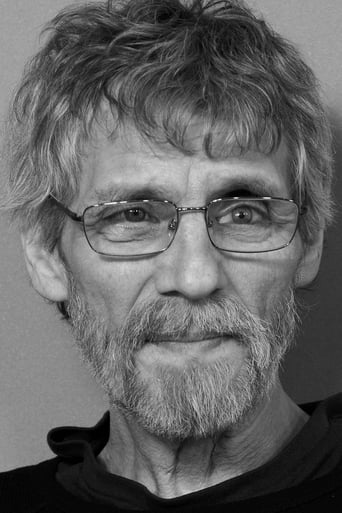

Hungarian screenwriter, producer and director Béla Tarr's eight feature film which he co-directed with Hungarian film editor Ágnes Hranitzky and co-wrote with Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai, is an adaptation of the novel "L'homme de Londres" from 1934 by Belgian writer Georges Simenon (1903-1989). It was shot on location in France and Hungary, premiered In competition at the 58th Cannes International Film Festival in 2007, was screened in the Masters section at the 32nd Toronto International Film Festival in 2007 and is a France-Germany-Hungary co-production which was produced by Miriam Zachar, Joachim Von Vietinghoff, Gábor Téni, Christoph Hahnheiser, Paul Saadoun and French producer and chairman of the European Film Academy Humbert Balsan (1954-2005). It tells the story about Maloin, a middle-aged railway signalman imprisoned by his vague prospects who lives in an apartment with his housewife Carmélia and his teenage daughter Henrietta in a port town. One night while Maloni is in his viewing tower, he witnesses a man with a briefcase being killed by another man on the dockside. After seeing the perpetrator leave the scene of the crime, Maloin walks down to the dockside and fetches the briefcase. When he discovers that it is full of English banknotes, he decides to hide it.Distinctly and precisely directed by Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr, this nuanced fictional tale which is narrated mostly from the protagonist's point of view, draws a quiet and incisive portrayal of a family man's internal changes after witnessing a murder. While notable for it's gritty and atmospheric milieu depictions, prominent production design by Ágnes Hranitzky, Jean-Pascal Chalard and Hungarian production designer Lásló Rajk, black-and-white cinematography by German-born cinematographer, film editor, screenwriter and director Fred Kelemen, fine editing by Ágnes Hranitzky and use of sound, this character-driven and narrative-driven crime story depicts an in-depth study of character and contains an efficient score by Hungarian composer Mihály Vig.This stylistic, dense and significantly atmospheric mystery about a man's moral conflicts and his relationship with his wife and his daughter, is impelled and reinforced by it's cogent narrative structure, subtle character development and continuity, esoteric characters, rhythmic pace and the fine acting performances by Czech actor Miroslav Krobot, English actress Tilda Swinton and actress Erika Bók. This austere, existentialistic and expressionistic neo-noir where the story at times becomes overshadowed by the cinematic brilliance, is a fascinating though alienating experience.

I started watching this film and after about 5 minutes, boredom set in. The boredom continued for another excruciating two hours. This should have been a short film of about 15 minutes instead, it's stretched needlessly with nonsense shots that seem to last forever - an old guy eating, the main character undressing and going to bed followed by darkness for what seems like three minutes, a butcher unconvincingly chopping a piece of meat, two guys dancing like imbeciles and on and on...While there are much worse films out there, this has to be the most tedious film ever made. This is the kind of film pretentious people brag about loving because they think it makes them seem smart and intellectual and deep. I'm sure understand it!", but let's face it, there's nothing to get here. I'd rather watch a marathon of Uwe Boll films than see another film like this. I think you should get a free t-shirt after sitting through this - one that says "I survived The Man From London"Stay far far away from this bs.

Tarr returns after a long absence. Unfortunately, it's not up to par. Well, I should say, I have much of the same problem with this film that I do with all of Tarr's films. I'm certainly not his biggest fan anyway. I love his aesthetic, and would definitely call him a genius just for his visual prowess. It's so extremely original. And he's so good at setting mood, although I should say that the mood of all of his films, at least his later, more well known films, is pretty close to the same. Dark, cold, lonely, the drudgery of life, etc. But as soon as the characters start to speak, I stop paying attention. I find most of the actual words of Tarr's films uninteresting, and, when the characters are talking, I start to realize that I don't find these people that interesting. They may look interesting, as Tarr captures their essence in severe close-ups, but they never say anything interesting. The Man of London unwisely adds plot to the mix. Tarr's earlier films have a wonderful meandering quality, where it feels like he's just capturing people going about their lives. That is true here to an extent, but this one has a pretty clear plot structure, and one that's been told often before: a man finds a pile of money that belongs to crooks, and he pays for it. It's not plot driven by any means, but that skeletal plot is followed, and it makes the film less interesting than Tarr's other films. Also, Tilda Swinton shows up as the protagonist's wife in what amounts to a cameo (she has about five minutes of screen time in this 2 hour and 12 minute film), and it's pretty distracting. There's a cute little nod to Satantango at one point, where people in a bar dance like they did in that behemoth. Also, the little girl with the cat from Satantango shows up as the protagonist's daughter. It's weird, because she looks exactly the same, except she's a woman now. A very, very creepy woman. Who probably still kills cats when nobody's looking.

The storyline is taken from a Georges Simenon novel, L'Homme de Londres (1934). In an interview in 2001, Béla Tarr avowed: "I believe that you keep making the same film throughout your whole life." His most recent work upholds this declaration, placing itself squarely in line with his previous feature-length films, especially Damnation (1988), Sátántangó (Satan's Tango) (1994) et Werckmeister Harmonies (2000). These four films share identical layouts of the credits, black-and-white film, minimalist dialogues, long scenes, and stories that are more suggestive than narrative in nature. Most of Tarr's actors are not professionals and several appear in different films, notably Erika Bók who is Estike in Sátántangó and Henriette in The Man from London. As for the handful of foreign actors, they are dubbed into Hungarian.If it was amusing to see Gyula Pauer play the innkeeper in two films, his third appearance in The Man from London indicates that the choice is deliberate. Same with the role of Henriette (Maloin's daughter), assigned to Erika Bók, who appeared as Estike (the child with the cat) in Sátántangó. In all of Tarr's stories, the innkeeper appears as one, single person. This is also true of Estike and Henriette who share a common destiny as child-victims. And yet Tarr only winks at us across the characters of different films; the most ordinary actions are equally allusions throughout all his works creating a universe of apparently insignificant habits. Maloin drinks in accordance with the same ritual as the neighbor-informer of Sátántangó. And when he throws a log on his fire, the stove in the first image of Werckmeister Harmonies springs to mind. So many habits in which the insignificant becomes significant because the images and the characters of Tarr's ceaselessly question one another: their existence is a succession of futile, routine gestures whose repetition bears witness to their vanity. Habits are simultaneously both their prison and their lifeline in the labyrinth of existence, giving them something to hold onto while, at the same time, preventing them from escaping their condition. True, the protagonists seek to purify their existence (Valuska), to change their destiny (Karrer, Irimiás, Maloin), to reverse the course of History (Eszter and his theories of sound). But they are inevitably reeled back in and crushed.Though the decor and the ambiance are consistent with classic film noir, the unraveling of the plot is so exact that two viewings are necessary in order to begin to understand. But, at the base of things, the story doesn't really matter. What Tarr shows us is less a criminal entanglement than the poles between which the characters oscillate. First there is the black and the white, admirably opposed in the first scene where half of the ship's body is illuminated. The screen is black at the beginning of the film; it is white at the end. The music is also bipolar. From the first notes of a long arpeggio, we believe we hear an organ, then realize it is the sirens of ships. In Homer's Odyssey, the song of the Sirens, inaccessible feminine creatures, threw the sailors off-course so that their ships ran aground on the reefs. Here, the song of the sirens is like a requiem. This dirge contrasts with the accordion ritornello, reminiscent of the inns in Sátántangó and Damnation. With Tarr, bistros are always places of escape where one re-creates the world, gets drunk, and devises the most absurd projects. The melody, acting as a setting for these hallucinations, allows death to be forgotten, but which the arpeggio obstinately calls back to mind. Its minor key and its infinite nostalgia only make it less able to elude destiny.Where does The Man from London fit into Tarr's works? In the first scene a shot twelve minutes in length the lens surveys and captures the entire space in a way unknown to the tracking in Tarr's other works, and shows, by its fluidity and freedom, at what point the characters are prisoners of their own gravitation. The camera seems to have wings so it may better watch the men and love them, without ever judging them. In this way, it is sister to Damiel and Cassiel, the two angels of Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987). Like them, Tarr's camera leisurely insinuates itself, beyond concepts of time, and penetrates the heart of beings, ready to capture each of their convulsions in a world where the only certainty is death, humanity's habit par excellence. Looking at the earlier films, several of the characters in The Man from London bring an unexpected contrast. Such as the Inspector Molisson, who seems above the law and alone brings justice. No other film of Tarr's has a main character so tenuously attached to the human condition. His behavior with Maloin and Mrs. Brown is Christ-like, in a manner of speaking. He consoles; he cleanses sins; he tries to console. In comparison, Mrs. Brown seems like Anna Schmid, Harry Lime's mistress in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949). Both women were used to entrap the man they loved. Both women, in the last images of the films, refuse compensation and disappear, dignity intact. In the end, Maloin, marred by sudden wealth, seeks redemption by turning himself in. He isn't sure if Molisson's pardon will allow him to find peace once again. The glass harp that punctuates the siren arpeggio as Molisson re-enacts the toss of the suitcase greets only Molisson's discovery of the truth. The final notes of the film, still played on the glass harp, mark the end of the inspector's work and the end of the riddle. Life continues for Maloin and Mrs. Brown with both their doubts and failures. But what makes The Man from London a new development in the works of Béla Tarr is the fact that this film brings together so perfectly cinematography, music, and plot line, creating a complete and emotional spectacle about the human condition.(Thanks to Jessica Alexander for the English translation!)