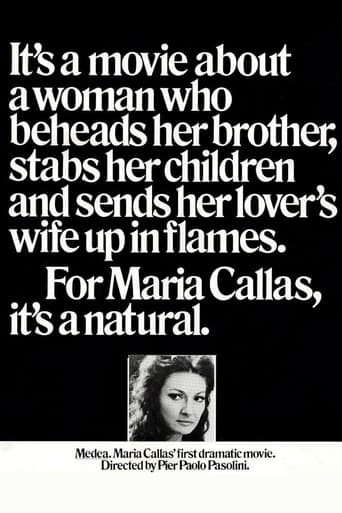

Medea (1970)

Based on the plot of Euripides' Medea. Medea centers on the barbarian protagonist as she finds her position in the Greek world threatened, and the revenge she takes against her husband Jason who has betrayed her for another woman.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

The music... same as in the other two titles of Pasolini that I have seen. There was a boy playing an instrument all through the film. And this music ended the movie, with Medea going crazy.Something of the camerawork I remember is faces that were out of focus, sometimes men's faces would be blurred in the eyes of Medea. This can show a perspective, how she didn't see Jason clearly for who he was.The killing of children, although implied, wasn't shown. I think that makes it even more powerful, because in the last scene Medea, reversely, caresses her children, lovingly.We see a sense of loss of her identity, first of all, because Medea doesn't even seem to realize how she kills her children. If we truly are put in her head, than everything is very chaotic, all over the place, all over the time. Guided by the strange music that a boy with her sons plays. Sometimes Medea will drift off, and then as she wakes up, we find out she has done something horrible, but not us, nor Medea, had any idea.When the maids undress her from the black clothes and put white gown on her instead, making Medea look like them, there is a sense of repression. Now that I think about it, this sense of repression is present in other Pasolini films too.It is also about how the repression breaks into a revolt. In Porcile, the boy is eaten by pigs, a repression replaced with extreme violence. Something similar in Oedipus Rex, where Oedipus destroys his eyes with metal sticks. As if throwing all anger and fear into one final move of hands. And the same happens here. The entire town is burning, the children are dead, and Medea is in the middle of all this with a black dress. Her repressed self has come through.

"Medea" reflects (some of) Pasolini's ideas about religion. He points out, accurately enough, that all religions we know today are successors to other, earlier religions. He also points out that religions interact : they fight, subvert, plagiarize, influence, nourish and transform each other. And quite often it's a case of "Plus ça change"... He expresses this concept by filling the movie with deliberate anachronisms : in Colchis, for instance, Medea and her family live in age-old dwellings, graven from the mountains, which at one time served as Christian churches or monk's cells. I can't say that everybody is going to appreciate these anachronisms but I for one did, I thought they resulted in a thought-provoking and artistically striking play of echoes and correspondences. So this is not a straightforward adaptation of Euripides' tragedy. For instance, much of the text goes out of the window ; indeed, bursts of speech or dialogue are few and far between. By the same token there is little in the way of classical classical costume. We, the viewers, are looking at the kind of ancient cultures - far older, even, than Euripides' own time period - whose practices, beliefs and rites may have inspired the various elements behind the Medea legend. The result is both familiar and vividly, dauntingly alien. Casting Maria Callas as the lead actress was a stroke of genius, since she possessed both majestic beauty and a general air of fierceness. One can well imagine such a woman taking sudden, sharp, cruel decisions and then executing them to the bitter end. (Watch out for the scene where the young Medea kills and then dismembers her brother : it's like watching a lioness systematically destroy her prey.) The actor playing Jason seemed inferior in talent, although he did succeed in capturing something of the infuriating opportunism and myopia of the character. An original, striking, electrifying work, but one that requires patient attention.

I recommend this to any adventurous viewer, but on conditions.Viewers who generally favor the clean, painterly versions of myth will find this amateurish, too slow and too cryptic in its ritual. A few even seem to believe that the repetition of the murder of Glauce and Creon is there by an editing mistake, imagine! But that's how sloppy it seems.Viewers who want the cutting conflict of the original play, will also be disappointed. There is a bit of conventional Medea in the latter stages of the film, but most of it is filmed in hugely elliptical swathes, so the concrete despair and drama all but evaporate in the air.It is a marvelously flawed piece to be sure, an appealing quality to me; that is not the same as being sloppy as a result of ignorance, on the contrary it shows an openness to imperfection, adventure and discovery. And this is a film about all three in how we watch this myth, but in what way?Let's see. A significant point behind the exercise, revealed in the opening scene where the centaur lectures a young Jason on the purpose of myth, is that we have forgotten what is vital in the stories we tell, the rituals we enact. Scholarly talk of ritual dance or meditation is as removed from the purpose of either as can be, obvious enough. This is certainly true of so many Hollywood films (and Cinecitta of course), and not just of the mythical or quasi- historical variety. Oh they may excite within narrow limits of the action, but..So many are filmed in the same way as everything else, they do not transport us, which for me is a prerequisite of every film but particularly mythic narrative. The dresses and headgear change from the norm, but the world and drama conform to a trite familiarity of other films. Though it takes place in strange, different times, a film like Ben Hur is filmed as static affirmation of visual and narrative norms; never more apparent than in the scenes with Jesus, presenting the passions in a stagy, painterly way we associate as real because the same images have been repeated for so long—say, the Crucifixion. Even Scorsese fell foul of this in both his Jesus and Buddhist films.So instead of giving us a vital presence in that world that will awaken a direct curiosity to know, they make us a dull spectator from a safe distance. We duly admire the perfection of the art and platitude of the lessons, the exact opposite of the nature of that story in particular, and spiritual insight in general. We see the mundaneness of the sacred, and not the opposite which is the spiritual essence—if we can't see transience in the traffic of Saturday night party-goers and can only read it from a Zen book, we've wasted our time.It seems this was in part why Pasolini undertook his Gospel film in the first place, show a world we know from fixed images with a real gravity that will invigorate a sense of intense, spiritual curiosity—the storylessons were the same, what changed was the air around the story.This is carried here. The point is that myth (by extension: the narrative and cinematic ritual) can only matter, be truly ecstatic, when it is really 'real' (not the same as realistic), which is to say something can only be vital when it escapes the routine of mind, and becomes 'alive' in the moment of watching. This is at the heart of the philosophical mind problem: structure does not begin to account for experience.So this is what we have here. All the effort goes to loosening up our sense of 'realistic' routine reality; the music is a mixture of Buddhist throat chanting, Japanese shamisen, Amerindian ululation, African tribal drums; the dresses and gear a mixture of Slavic, Maghrebi, Greco-Roman origins. At this point, you'll either think of it nonsensical or begin your immersion beyond sense. The point is that this is a hazy world a little outside maps and time, undefined yet. But within this world, Pasolini creates an experience of intense 'being there'—in his camera, in his chosen places and fabrics, in the textures of light, it feels like we are present. Oh it is still an abstract ritual, but one that has sense, and that sense is carried entirely in the air of the film, not in any spoken conflict.Further within the ritual, we have Medea's own magical timeflow of conflicting urges and dreams, channeled by Callas channeling her own anxieties with fame and husband, inseparable from all else. Her presence is so intense, it may be creating imaginary madness in a key scene—this seems to be why we see the burning Glauce in the dream but not out of it. The bit with the centaur may be silly, but that is Pasolini telling us a bit about the film he's made. The rest is so, so wonderfully conceived. The opening with the boy touching the sacredness of nature in every small thing is like out of Malick, 25 years before. During this time, Pasolini was perhaps the only one (with Parajanov) who could rival Tarkovsky in his cinematic flow.

"Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned" describes Medea, whose hubris and amour fou for the bold and beautiful Jason leads to her downfall. Revered as a goddess by her own people, she betrays her own divinity and her race when she aids him to steal the sacred fleece, killing her own god-brother by decapitation during their escape. After bearing two sons to Jason in Greece, Medea is still not accepted and fails to adjust to Greek culture. The affection of acclaimed hero Jason strays and his ambition culminates in a betrothal to King Kreon's daughter. But when Medea learns of this betrayal and negation of her love and sacrifice her fury knows no bounds. She summons up the dark forces within her (she is a barbarian sorceress after all) for vengeance against those who have wronged her by killing Jason's sons, welcoming him with a false semblance of conciliation and acceptance while serving his dead sons to him for dinner. She sends two magnificent marriage cloaks to the king and his daughter who, when they don them, burst into flames. She then departs in rage leaving Jason to live with the results of the infamy he caused her enact through destroying her life. Maria Callas, in her only film, shows the famous range and subtlety she enjoyed as an opera star. Her fierce control and rage are memorable. Although this was a low budget film, it is extremely evocative and leaves lasting impressions. The sequence in the beginning when Jason was being tutored by the centaur Chiron about his destiny was very effective, and marked the innovative trick-photographic technique of melding man to horse to make it look very real and convincing. The primitive settings and human sacrifice of Medea's people helped to establish her dark, powerful and exotic barbarian character. English subtitles helped make up for the unfortunate dubbing. A strange and powerful version which holds it own against other interpretations.