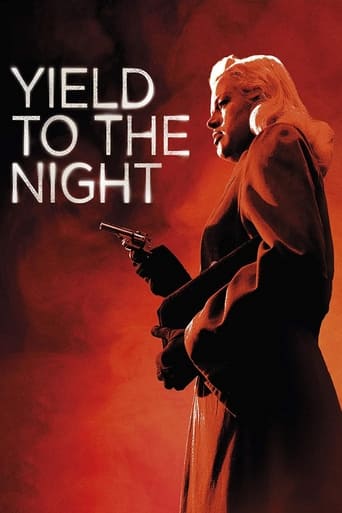

Broken Blossoms (1919)

The love story of an abused English girl and a Chinese Buddhist in a time when London was a brutal and harsh place to live.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Great movie by the pioneer D.W. Griffith. It is beautifully filmed (including the quite realistic boxing footage) and has really amazing performances by Donald Crisp as the violent alcoholic misogynist boxer Battling Burrows and Lillian Gish as her suffering daughter Lucy (white Richard Barthelmess, though, does not convince so much as the "yellow man" from China). Although with a naive idea of an always peaceful Eastern spirit, it denounces xenophobia and - very curiously - racism. Besides that, by portraying domestic violence it also denounces misogyny. The story begins in a slow pace showing the contrast between calm Chinese people and brute Western sailors. Years after the "yellow man" comes to London slums, he knows a charming girl whose life is a hell, as her father alternates between boxing, drinking in the bar, and beating her at home. Then, what had began monotonously is turned into a storm. I have not watched "Intolerance" yet, but this is my favorite film by Griffith, author of infamous "The birth of a nation", by far (I have also watched "A Corner in Wheat").

Broken Blossoms is arguably the best film that D. W. Griffith made. Although it is a silent film, it has an engaging story that does not suffer from a lack of dialogue. Furthermore, unlike Birth of a Nation, it has a message of racial tolerance that still resonates today.The film follows the course of a man from China who travels to the West. Perhaps because of the controversy surrounding Birth of a Nation, Griffith goes out of his way to depict the immigrant in a positive manner. Unlike the story it is based on, in which the immigrant is a typical dissipated sailor, Broken Blossoms has its protagonist come to the West in order to spread the peace and good will of Buddhism. Indeed, all the European characters, with the exception of Lillian Gish, come across as savages compared to him.Broken Blossoms benefits from several good performances. Although she is rather old for her role, Lillian Gish manages to convey a sense of innocence and vulnerability. Donald Crisp is suitably intimidating as her abusive boxer father.The film also deserves kudos for being well ahead of its time. Not only does it have a relatively progressive stance on race and immigration (keep in mind the Chinese were barred from immigrating to America at this time), but it also deals with issues of child abuse. The depictions of Crisp's attacks on Gish are genuinely harrowing, with at least one scene seeming to imply that sexual abuse is going on.For all its good points, the film has some flaws. Although Griffith specifically called for color tinting to be added to the film, it seems more a distraction then a benefit. Furthermore, the use of a non-Asian actor, Richard Barthelmess, to portray the immigrant is embarrassing in hindsight, and undermines the film's overall message of tolerance. Nevertheless, Broken Blossoms is still a film masterpiece that is well worth seeing even ninety years after it was made.

D.W. Griffith is a genius. A clear innovator to the art of motion photography. D.W. Griffith is probably one of the most important filmmakers in the history of film and this astonishing silent, Broken Blossoms is a clear indication of why. The style of acting portrays the young stages of conveying emotion and mood through a camera narrator. This film is by far one of Griffith's finest. The decor looks incredible, the costumes are superb and the mise-en-scene is very sophisticated, especially for it's time. This film really demonstrates the beginning of cinematography as well. Every shot from this wonderful picture if paused would look like a conventional photograph from that time period. But being played out as a film makes it that much more intriguing. This silent masterpiece was incredible to watch.

Broken Blossoms was a strikingly beautiful and enthralling film. It portrayed an intense, and somewhat dangerous love story. The music that accompanied each scene was appealing to the ear, more so than some other silent films. The colors(tints) used to expose detail in each scene were also impressive. Similar to The Gold Rush, the characters expressions and body language really displayed the feeling and story in the film, however, there were points where the acting was a little too dramatic, or lacking thereof. All in all, The film was well directed and written, it seemed as though it may have been a little provocative for its time, but I can appreciate Griffith's(the writer) willingness to write a film like this. Without those daring to go against the majority, there would be no progress in society.