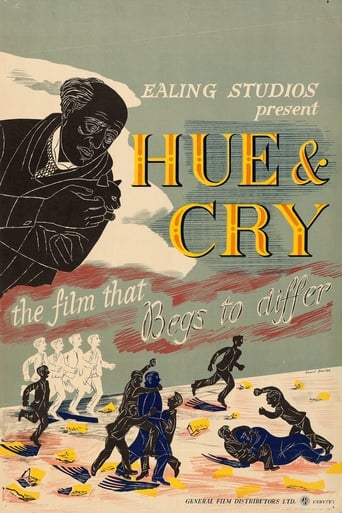

Hue and Cry (1947)

A gang of street boys foil a master crook who sends commands for robberies by cunningly altering a comic strip's wording each week, unknown to writer and printer. The first of the Ealing comedies.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

From director Charles Crichton who made the classic A Fish called Wanda in 1988 is this early effort from 1947, Hue and Cry.A crime caper focussed on kids who discover a criminal ring that are using a comic strip to send instructions to plan their jobs.Joe Kirby (Harry Fowler) is a lad who is always in a spot of bother. He is placed by a policeman for a job with a Covent Garden grocer Nightingale (Jack Warner) who listens to his stories of a fur smuggling ring with a filthy laugh.Felix Wilkinson (Alastair Sim) is the scatty comic strip writer who stories are being manipulated by an insider in the publishers. As the police does not believe Joe's fantastical tale, it is up to him and his gang to take on the crooks.I must have first watched this film as a teenager. It rather reminded me of those Enid Blyton adventures I used to read as a kid. The post war setting of a bombed out London make the city look like an adventure playground for kids.It is an enjoyable Ealing comic adventure as the kids take on adult crooks and put themselves in jeopardy. Sim gives an amusing cameo.

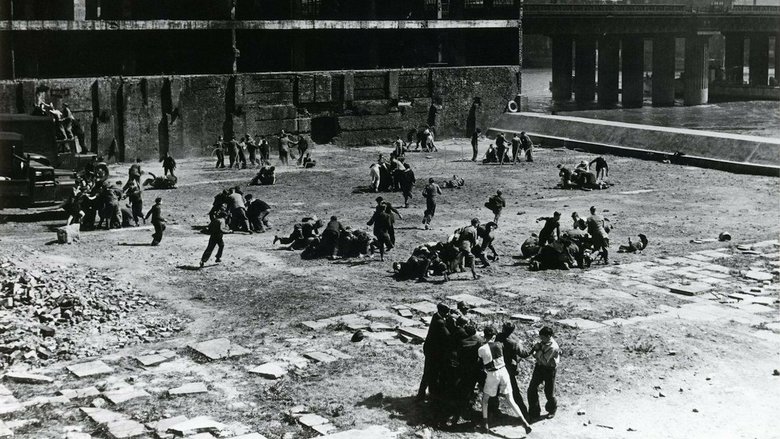

HUE AND CRY tells a straightforward tale of how the Blood and Thunder Boys, a gang of teenagers led by Joe Kirby (Harry Fowler) foils a plot to smuggle illegal furs led by his boss Nightingale (Jack Warner, cast engagingly against type as a villain). On the way Kirby encounters a variety of lowlife characters including good- time girl Rhona (Valerie White), crooked shop-owner Jago (Paul Demel) and a spiv (Joey Carr). Yet Joe emerges triumphant, not least because he is assisted by a large gang of youngsters, including Scot Alec (Douglas Barr) and Rhona's work-colleague Norman (Ian Dawson). The film contains a memorable cameo from Alastair Sim as Felix H. Wilkinson, a scatterbrained writer of lurid popular fiction who tries to charm Joe with a glass of ginger pop but is eventually blackmailed by the teenager into helping solve the crime.Perhaps the film's greatest asset, however, is the way in which director Charles Crichton uses the locations of war-torn London to tell his story. The Blood and Thunder boys have their hideout in a bombed-out building, full of secret corners and ruined beams for them to play in. As they pursue Rhona along the London streets, we understand how shabby the city looked at the time of filming, with very few commodities for sale in the shops. The city was also highly socially stratified, with stark contrasts between the poky terraced houses where Joe's family live and the expansively appointed detached houses in the suburbs (most of which received comparatively little damage during the Blitz). On the other hand London was much quieter at that time; very few cars adorned the streets, and horse-drawn carts were still very much in evidence, used mostly by tradespeople.Despite its basic good humor, HUE AND CRY offers a radical vision for post-war Britain. It suggests that the old social order, where children should be seen and not heard, has collapsed; anyone can now achieve their aims, so long as they are prepared to fight for them. Director Crichton also suggests that postwar London is also a center of petty crime; a combination of stringent rationing and lack of availability of fancy goods provided a rich hunting-ground for black marketeers such as Nightingale. Yet perhaps people had a right to expect something more - after all, they had just spend six long years fighting for their freedom. Crichton offers the possibility of a solution by showing the children triumphing - perhaps youth will help to usher in a brave new world of prosperity.

Today 'Hue and cry' stands as a fascinating socio-cultural document of post-war Britain, shot in location in the East End, around Covent Garden and in some of the ruins left from the Blitz. It not only is a quite entertaining and exciting boys' adventure but it also shows us what British teenagers were like in those days. Many of them were already earning their bread because the times were hard and many families had lost their men in the war. Also, having not the means of entertainment the boys of today have (television, motorbikes, computers...) meant that boys then were always in the street and often had some special meeting place out of the adults' sight where they idled for hours without doing anything in particular. Apart from cinema-going, the only source of popular entertainment they had were comics. That was the golden era of the Eighth Art. The film benefits from a very imaginative script. The implausible story is yet engaging and has moments of fine suspense: Kirby sneaking into the furrier's shop to inspect the suspicious-looking crates, he and Alec creeping up the staircase to Alistair Sim's flat, his realisation of the mastermind villain's identity and the final confrontation at the bombed office block by the river. A fantastic cast of talented youngsters, humour, suspense, lots of excitement and a marvellous Alistair Sim in a ten-minute appearance that nevertheless plays a key role in the story. A film that may look very outdated now, but still great fun to watch, and definitely a landmark in British post-war cinema.

The word 'hue' is Middle English (derived from Old French) and means 'to shout or make an outcry'. 'Hue and cry' derives from the Anglo-Norman French dialect of a thousand years ago, 'hu e cri', and describes the outcry made to call for the pursuit of a felon, or the pursuit itself of such a criminal. By extension, it came later to be applied to the noise, blown horn, and shouting made when English hunters and their hounds spotted a fox and set off in pursuit of it. At the time this film was made, 'hue and cry' was a phrase known to everyone in England and was frequently used in conversation. It only died out in the 1980s. Before that, if there were a big fuss in the press over some political issue, people would say: 'What a hue and cry there has been in the papers today about the Prime Minister's policy,' or if justice were not seen to be done, they would say: 'They have set up a terrible hue and cry over that issue recently in legal circles'. In other words, by the 1960s 'make a hue and cry' had come to mean 'make a loud fuss'. It was a phrase that was used daily all over the country for decades, but is now as forgotten as the dodo, since most of the people who used it as a common expression are dead, and they did not perpetuate this usage amongst their children, who viewed it as old-fashioned, and dropped it. This film was shot on location in 1946 in London, and gives mind-boggling views of the extent of the ruins left after the wartime bombing. Anyone familiar with London simply gasps with disbelief at shot after shot of rubble and collapsed buildings, in which this gang of street kinds regularly play. The ruins are as extreme as those of bombed-out Germany which were shown in the newsreels and recur in documentaries about the War today. Seeing how extensive the devastation of London really was brings the issue of the British Bomber Command into better focus, and reminds us that the decision to bomb the German cities as flat as pancakes had something to do with rage. War is war, you know, a point often forgotten in our spoilt age of today. People today seem to think that war can be fought remotely with drones, or that war is something which takes place in distant deserts and mountains. But take the contemporary American outrage at 9/11 and multiply it by a thousand, and you will get some idea of how the British felt about the Germans, and many still do ('bloody Krauts, now running the European Union as a Fourth Reich!' as I have heard it said). So this film has an importance far beyond its story line, which is a charming one about children bringing criminals to justice and setting up a hue and cry about them when the police can and will do nothing. The one portion of the story which is really rather silly is the character of the writer of children's' comics played in an over-the-top doddering fashion by Alastair Sim. That was terribly overdone, and the excess of whimsy makes one queasy. The story involves children's comics being doctored to carry instructions to real criminal gangs for their next robberies, hence the children figuring it out and taking action. The British have always been inclined to believe that secret coded messages were carried in their newspapers. Harry Jonas the artist and Walter Sickert's illegitimate son whose name I have now forgotten used to tell me that the secret to Jack the Ripper's identity had been revealed in the crossword puzzles carried by the Daily Mail, which was also used to convey coded instructions to British secret agents. They believed all of this absolutely, and I have met others who did. The Americans thus do not have a monopoly on paranoia and conspiracy theories, as these were widespread in Britain long before they became fashionable in the USA. Here we have an entire film released in 1947 based upon one, and a semi-comedy at that. This film, an Ealing production, is often called the first Ealing comedy. I would not call it a comedy per se, but it has a definite comic side to it. Nor would I call it a fantasy film, as the setting and the kids are too 'real' for that. Many of the kids do brilliantly, especially the one tough street girl amongst the gang of boys, played by the truly inspired actress Joan Dowling, in her very first screen role at the age of 17 (she died at the age of 26). These kids represent the authentic Cockney tradition of the East End of London with their self-reliance, cheekiness, irreverence, and daring, and much of the action takes place at Chadwell near Tilbury in the East End. (An ancestor of mine lived at the manor house of Chadwell, called 'The Long House', in the seventeenth century when it was all farms, strangely enough. But it subsequently became a Cockney slum area when London expanded in the 19th century.) The film is superbly directed (except for the Alastair Sim sections) by Charles Crichton, whose last film which he directed at the age of 78, was the hilarious hit, A FISH CALLED WANDA (1988). He also directed part of the great classic film TRAIN OF EVENTS (1949, see my review, and my comments there about the spectacularly brilliant actress Joan Dowling, mentioned above), and is famous for THE LAVENDER HILL MOB (1951). Another extraordinary aspect of this film is the section where the kids wander through the London sewer system, which I have never encountered in any other British film. Everything about this film makes it worth watching, and certainly enjoyable for anyone who does not require continuous 'smash bang' on a drip.