The Regeneration (1915)

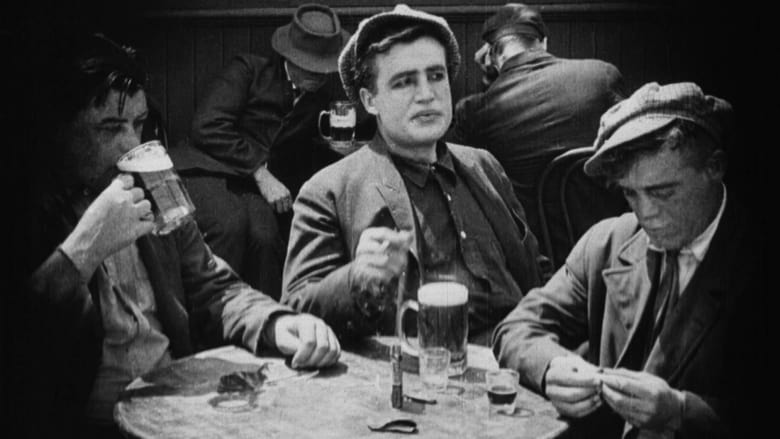

At 10 years old, Owen becomes a ragged orphan when his mother dies. Abusive next-door neighbors the Conways take him in, and by 17, Owen has learned that might is right. At 25, he's a career gangster: loitering, gambling and drinking in dens of iniquity. Marie Deering arrives in Owen's area, eager to empower the impoverished, gang-affiliated youth through education. Owen slowly but surely leaves his old life behind, choosing the narrow path- all the while falling in love with Marie. Skinny, who's taken over Owen's role in the gang, reappears to him, spelling trouble.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Reviews

Walsh had much more spotlight subsequently. Can we ever forget "White Heat", "High Sierra", "The Roaring Twenties"? He's the reason John Wayne is on the map and he has worked in a vocation where he has given many actors their magnum opus, and moreover, he's one of the directors that inherited story before methodology.The role that he left an indelible impression on me, was his portrayal of John Wilkes Booths. He was a harrowing figure in it, and aptly it worked as he had just started off acting, and was probably the right age to give the portrait a verisimilitude. The time, place and cause and effect were balanced by a brooding canvas in historicity; a momentum of perfection.The same year, he graced his own project to the screen. It's 96 years old and has barely withered its original acetate (despite being heavily smudged on blue tints of the negative especially near the beginning when Owen goes and gets a bucket for his dipsomaniac adopted Father. But a lot of it is fairly pristine.The film is based on a book about a young boy Owen. As we go through the pervasively impressive film there's one thing for certain - it's a commentary on the civilisation of susceptible parents and their malicious effect to this young adopted boy. It reflects later on when Owen saves a boy, who Marie Deering (a girl who works in Grogan's and then is drawn to his joint). The period periodically changes and we're then lead to believe that he has ran down to the lowest status in a derelict area. Potent in the way it's looked at, we watch a society without poise, were fighting is ample in mustering entertainment.The character of Owen and the regeneration of his clique is hellbent on the omnipresence of Marie Deering; she aids Owen in his studies, influence and loving compassion. She's the thing that also destroys him; he never reconciles in the gang he originally lead and they're causing a havoc with their abuse of Police and their brutal comeuppance. One bit that's sort of disjointed from the narrative, is when Marie Deering during the second act, invites him and his Friends into a party and throughout it Owen leers at another woman, who's docile and unfazed. He then throws his cigarette on the boat, unbeknownst that it burns. I guess the scene was used as a visual provocation, yet it still does leave a grand and lyrical impact inherent. It's also perhaps a way of uniting them all and separating it later.It's a deep film. The seminal Gangster film has a lot of heart, and you can even sense its seminal films on such films as Howard Hawks' "Scarface", "The Public Enemy" and his own film "Roaring Twenties". The manipulation of lighting to emphasise by masking the gun or dissolving is not dissimilar to how it's done today. Though the way it's used here is a bit more vivid, looking at the way the officious guy is introduced to the scene, where Marie is working, to entice us with important plot points. The most impressive of these sequences is an abrupt scene where a Gang Member is harassed by an Officer and takes out a knife to go in for the coup de grace. Most films would chiefly employ blood to give it the verisimilitude - the realism to set it apart - here though, to keep its gritty and taut realism, Walsh uses off screen cutting to let the Audience comprehend the outcome.It's probably fundamentally great to understand, like Fleming with his primitive films, that Walsh was just a disciple of Griffith, who he was influenced by (watch "The Muskateers of Pig Alley") and his literary influences (this film was adapted from Owen Kildare Frawley's "My Mamie Rose" autobiography, which hitherto I was startled to find out that the film was reciting a time of an actual boys life and memoirs to accompany it, making it, of even more valuable commodity).The thing is, the character is visceral and not intellectual. The story grows in a cerebral way, and does not descend to ruthless violence, probably because it would have been harder to sell. But in a way, it's adscititious; it would be faltered in its tone and focus.Another thing that will definitely jolt audiences today is the fact that the film relies on visuals. If when looking at the narrative through the camera, you actually notice that in fact, your mind gives the character their contours. You have to understand the struggle - with other films to justify it all seems pretty well grounded in the genre of its tradition - and it will not leave you with disappointment.While not epic, the film is a character study, a utopian and dystopian story - truly taut, hard, stylised, with little bits of emotions and a veracity.

Rather than repeat what others have written, I'd like to comment on how this film managed to get into circulation.The only known print of the film was found in the basement of a building in Montana in 1976. Preserved (and not too soon given the deterioration seen in the middle of the film), it was part of a series of films shown during the New York Film Festival representing titles which had recently (1978) been saved. I remember seeing all of them; they included Lillom (recently issued on DVD in the Murnau/Borzage box and worth seeing), and The Letter (with Jeanne Eagles, which blew everyone away). It is a miracle that films still turn up in such a manner even this late in the game. Most films from this time period have long ago turned into flammable dust (they started to deteriorate as early as the thirties), and it is particularly fortunate that "Regeneration" is now among the living. Despite its crudities, it feels like a documentary of the seedier elements of New York, and it still works its magic; it has matured very well. Given that we can see how the streets of New York really looked almost 100 years ago, the film may play better than it did back then. Most of the people in this film are not actors, they are real people, and that is what we reacted to when we saw this back in the seventies. Additionally, the film is a real window into the transitional period when the one-reeler had turned into a longer, more ambitious feature. As a first feature for Walsh, this film is really extraordinary when we consider that the tools of film-making were still crude (the comments on the editing of the film are correct. However, the abruptness plays better on the big screen). Even more, the film also reminds us that the numerous features made between 1914 and 1920 included some real gems that are gone forever, and cannot be re-evaluated. How many really good actors and directors are known in name only because their work has disappeared?I consider this one of the finest examples of an early silent feature, and one of the landmark films of the silent era. It is an illustration of how the director of that time found his or her way, made mistakes and had chances to improve. It shows how filmmakers were taking the vocabulary used by Griffith and some European filmmakers to expand the techniques of storytelling to hold an audience's interest for an hour's worth of entertainment.A must-see if you are interested in silent films.

In cinema, 1915 is best known as the year of DW Griffith's epic Birth of a Nation. While I won't play down the talents and achievements of Griffith, his debut feature was merely a culmination of his prior achievements, a milestone in cinema culture but adding nothing to cinematic language. Regeneration however, a largely overlooked film (although it has its champions), was perhaps truly the most important picture of that year.Raoul Walsh, previously an assistant to Griffith, and already having a handful of short features to his name, made his full-length debut with this romantic gangster fable. The picture opens fairly conventionally for the time, Walsh displaying an incredibly firm grasp of film form for such a young director. The opening shot establishes the mood - the recently bereaved protagonist sitting alone in a bare room, a curtain billowing forlornly behind him, after which we cut away to the hearse bearing his mother in the street outside. However, we then see the lad go to the window and look down. In the very next shot, the camera is looking down at the hearse, exactly as he would see it. Bam! The point-of-view shot is born.The point-of-view shot is not merely a convenient alternative angle for storytelling. It places the audience into the position of the character. It's something unique to cinema you can't recreate that in the theatre. The only real equivalent is in novels, when the narrative is told from a character's perspective. Walsh here gives cinema that ability, and moves the audience from the position of spectator to that of participant. It's particularly apt too for Regeneration, as it was adapted from an autobiography. Walsh remains consistent to the story's roots by primarily showing the points of view of the protagonist, Owen.Another great thing about Regeneration is its use of dolly shots that is, moving the camera in or out, towards or away from the action. This wasn't an innovation as such, the dolly having been invented by Giovanni Pastrone for his 1914 epic Cabiria, but the dolly shots in that picture are largely uninspired, at best creating smooth transitions between different length shots. Walsh however really explores the possibilities of the technique. First he uses it to home in on the young Owen in the scene where his adoptive parents argue over the dinner table. Again this is a move which draws us into the character's world, as if we are being pulled forward and forced to look. Much later, in the scene where Anna Q. Nilsson bursts into the gangster's den, the camera itself rushes forward, reaching the centre of the shot at the same pace she does. In effect, the camera movement mimics hers and gives the audience a little taste of her sense of urgency.Needless to say, there is a lot more to Regeneration than these pioneering camera techniques. Walsh's handling of the dynamic moments is particularly adept, with a climactic ride-to-the-rescue worthy of Griffith, and some particularly realistic fight scenes. But he was just as capable of great tenderness as he was of great action, and the picture is shot through with the sense of melancholy romanticism that is typical of Walsh. And let's not forget the fine naturalistic acting on display, although stars Rockliffe Fellowes and Anna Q. Nilsson would soon fade into obscurity.By way of a disclaimer, I should point out that Regeneration may not literally be the first motion picture to use point-of-view shots. There was, after all, a wealth of experimentation in the early days of cinema, and many films are obscure or lost. It is shortly after this though that the technique seems to enter mainstream usage. For example, Cecil B. DeMille's The Cheat, made several months after Regeneration, features point-of-view shots, whereas DeMille's Carmen, made about the same time as Regeneration, does not. Tag Gallagher, in his superb essay on Walsh for Senses of Cinema, makes similar claims. Whatever the case, Walsh certainly excelled in a new kind of cinema, one which placed the audience inside the story, and this principle would shape much of Walsh's work throughout his fifty-year career.

By the standards of its time, this is a better than average film, and it is still watchable, even though the social and cinematic conventions of 1915 may make it rather quaint to some viewers. Still, the theme about a good woman regenerating a rascal is not unusual today, and here it is told with coherence and simplicity.One may find the acting style quaint, too, but some of the worst excesses of the silent days are avoided for the most part. Perhaps we can thank young Raoul for that. The editing is choppy, but that may be due to losses over the years, and it may vary depending on the print or tape translation one sees.