The Big Heat (1953)

Tough cop Dave Bannion takes on a politically powerful crime syndicate. Preserved by the Academy Film Archive in partnership with Sony Pictures Entertainment in 1997.

Watch Trailer

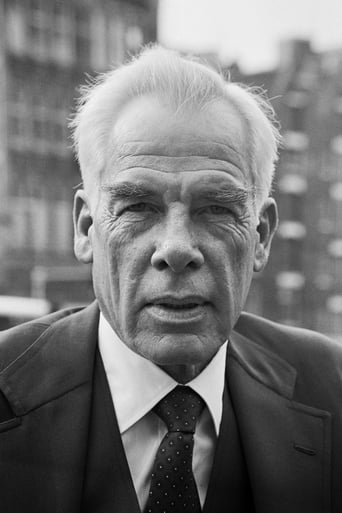

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

A deeply satisfying noir, with a gritty cop (Glenn Ford), femme fatale (Gloria Grahame), and powerful crime bosses (Lee Marvin and Alexander Scourby). I love how hardboiled this one is, with Ford becoming suspicious after some discrepancies in a fellow cop's suicide, and a woman getting viciously murdered. He's soon fighting upstream against a wave of corruption, and then getting threatened himself, but I won't say more about the plot. All of the performances are terrific. Ford is a sweet and decent guy with his family, brave and unflinching in confronting evil, and tough when he needs to be - tiptoeing along the line of being too tough in some cases, the moral ambiguity of which is interesting. Grahame is just delightful, particularly in the scene where she shimmies about during cocktail hour. Of the villains, Lee Marvin plays a sadist very well, and is explosive in every scene he's in. Director Fritz Lang harnesses it all well, including the strong script based on William P. McGivern's novel, and the pace is perfect. I loved how the film was clear enough to follow, but at the same time, had quite a bit of depth to it. Great stuff, and clearly influential.

Fritz Lang's The Big Heat is among the best noir movies ever made, and unlike any noir movie that I have ever seen before in my entire life. As the movie opens we see a corrupt cop commit suicide and then within a few seconds his wife comes downstairs to see what had happened and she finds her husband on his desk with a pistol in his hand and calls the police. Thee movie stars Glenn Ford as Police Detective Sergeant Dave Bannion the man who is in charge of this investigation of the apparent suicide, then within a few days Bannion is ordered to stop asking the wife of the dead cop questions about her husband. While trying so hard to crack this case right open he continues persistently until an explosion in his car happens for him ended up killing his wife (played by Jocelyn Brando, who was the sister of Marlon Brando) instead. Then Bannion permanently resigns from the police force and finds out that all of this was planned by the mob underworld led by Mike Lagana (played by Alexander Scourby) as well as his abusive henchman Vince Stone (played by Lee Marvin), then when Vince's wife Debby Marsh (played by Gloria Grahame) Vince then disfigures half of her face with hot coffee, and then Debby is more than ready for payback by telling Bannion all about Vince and all his other mob friends and what they did all along and the cop suicide case was a cover up. Theis movie compares to classics in it's genre such as Touch of Evil (1958), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Big Sleep, and some of Alfred Hitchcock's best films. What a great film this was.

Interestingly enough, I started to get into the film, mostly because of the Mes En Scene of the 50's and the props, automobiles and language that was from the era I grew up in. The motifs were things that have long since become relics like the old rotary dial phones, cat clocks, mink coats and beat-nick artwork. The liner narrative of Big Heat has a three-act structure, with the inciting incident of a tip to the law following the suicide/murder (?). As the clues roll in for detective Bannion, the development of each character defines subsequent developments. Questions to arise, especially since "Tom had no reason to kill himself" and "Then why did Bertha's husband kill himself if he was in good health?' By the second act the protagonist had more questions and doubts about the reliability of the cast. Act Three Debby Marsh, the typical Femme Fatal has revealed a not so innocent character, closing doors with open-ended pondering like, " Do you get your kicks walking out on people She and Dave leave together in a taxi to his place. This binary opposition of family vs. the corrupted individual is intertwined throughout the final act where the plot unravels and all his well traveled wife wants to do when things get tough is go out and get her legs waxed.Dave Bannion is a typical patriarchal, hard working detective, married to a self centered and not so innocent wife, who admittedly isn't a romantic. He's got the garb, morality and motivation to find justice on either side of the law. Dave and his supporting characters all act like they are in control, when in actuality they're barely keeping up with the Jones and fall in step way behind the dominant dames. Debby, Dave's beautiful, but deceitful wife looks for revenge, while displaying a classic Femme Fatal character, or should I say, lack of one. She is rebellious, manipulative and pretends to be something she's not, in order to get her way. Mrs. Duncan acts and plays the part of a distraught widow, but curiously isn't emotional after her husbands supposed suicide, yet in order to tug at the heart strings of the investigator, Bertha hams it up and pretends to be out of sorts when the detective candidly asks her, " Do you know why he'd (her now dead husband) take his own life?" _ " Oh", she answered, " he's complains about his painful hip", as though she was offering some kind of inside scoop about why an otherwise healthy and happy man, up and kill himself. As a Femme Fatal would be expected to do, Bertha twists her alibi and blames some other woman. One of many "Lucy's or mistresses in her unfaithful and deceitful husband's life. Debby wasn't the only Femme Fatal in this film; Debby March knew how to wrap men around her little finger without being childish. Rather, she was sexy, desirable but unreliable and dark. Like the other women in this film who all seem to fit the MO of a Femme Fatal, Debby is manipulative and willing to use men like Vince Stone for their money and luxury. They are motivated to do wrong.Comparing and contrasting the relationships brings to light the homogeneous bonding between the investigators and even the commissioner. Their costuming is similar and even though they share a conflict of interest, on the surface they all seem to be hard working patriarchal men. The opposition of that of course is the Femme Fatale who tries her darnedest to confuse the truth and avoid being found out as the crook she is. Also, how everyone is ready to double-cross whoever they need to in order to squirm out of the immediate predicament.

The Big Heat is a prime contender for the cruelest and most brutal of all film noirs, which is saying quite a lot. At the same time, a big part of why that may be so is that The Big Heat is in many ways hardly a film noir at all. All of the great canonical film noirs, including Otto Preminger's Laura, Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity and Ace in the Hole, Jacques Tourneur's Out of the Past, and Alexander Mackendrick's The Sweet Smell of Success, tend to be populated by characters with little trace of goodness left in them; they are all doomed, fated to their inevitably bitter ends from the outset. What makes The Big Heat so powerful and disturbing—and, ultimately, so unlike most film noirs—is that it has, at its heart, many genuinely good people.Fritz Lang, the brilliant German director who had already cemented his place in cinematic history with monumental films like Metropolis, Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, and M, creates in The Big Heat a film whose strength lies in defying expectations of plot, genre, and characterization. Its opening, for instance, is not a far cry from the usual hard-boiled detective formula. Police Sergeant Bannion (Glenn Ford) is assigned to investigate the suicide of a high-ranking fellow officer, which leads him to uncover a trail of corruption and licentiousness and, in turn, puts him into deep trouble with the local mob syndicate, headed by Mike Legana (Alex Scourby) and the psychopathic Vince Stone (a young Lee Marvin).Lang manages to transcend these cut-and-dry foundations, however, by affording his protagonist a greater depth than one usually finds in a hard-boiled detective hero. The typical hard-boiled detective is unshakeable, wisecracking and ethically-ambiguous, but generally one-note: coolness is all they have going for them. Glenn Ford's character, by contrast, is a family man and, ultimately, a tragic figure. Whereas the characters in other film noirs are often so uniformly reprehensible that any misfortunes that befall them seem almost warranted, the juxtaposition between Bannion's tough policeman persona and his fatherly sensitivity and protectiveness—first with his daughter and later with Stone's abused girlfriend Debbie (Gloria Grahame)—makes the character's plights and perils all the more involving. You see, Bannion is not just a smart-talking male power fantasy, but a decent, honest man who is merely driven to brutality by tragic circumstances.Perhaps the reason that The Big Heat seems so sadistically violent, then, is that the audience is given genuine reason to sympathize with those who are subjected to it. Again, this is where Lang's genius really comes into play. Anyone who has seen enough Hollywood movies would naturally expect that after Bannion carries his unconscious wife (played by Marlon Brando's older sister, Jocelyn Brando) off-screen after she has been wounded in a car-bombing intended for him, there would be a scene in which we see her safely recovering in a hospital bed and Bannion angrily promising her that he will find out who was responsible for the attack. But no: in the next scene, we find out that she dies. On top of that, Lang mercilessly obliterates the quaint, idyllic domesticity of the Bannion household in earlier scenes with a scene in which Bannion bitterly packs up and moves out of the old family home, now cold and empty. It's truly heartbreaking, and it makes Bannion's subsequent trials all the more compelling and, dare I say, poignant. The same goes for the infamous scene in which Lee Marvin scalds Gloria Grahame's face with a pot of boiling coffee. The scene is especially cringe-inducing and sadistic because the audience realizes that she is not just some vain, self-obsessed gangster moll (which, in a more conventional film noir, would make the cruel attack seem like poetic justice), but merely an unlucky, good-natured girl who got caught up with the wrong kind of guys.The rest of The Big Heat then works like the best of revenge tragedies, in which even more cruelty and violent retribution is enacted as form of catharsis. The one thing that struck me the most about the action in this film is just how much more forceful and yet satisfying it seemed. Just like any hard-boiled hero, Bannion goes around and punches the lights out of a lot of henchmen throughout the film. Under Lang's direction, though, the punching in The Big Heat doesn't have the stagey and almost slapstick-like physics of other cinematic punches, with the bad guys awkwardly stumbling backwards or flipping over tables. Instead, when Bannion punches somebody, they practically fly across the room, knocking everything down in their path. That Lang often quick-cuts or whips the camera around in tandem with the physical blows gives an even greater illusion of weight to the action. Furthermore, not only does Bannion punch a lot of people, but he strangles quite a few people too, including one of the female antagonists. It is here that I must give due credit to Glenn Ford for his performance here: he is not just good; he's scary good. Again, the fact that Ford is capable of showing Bannion as both a loving family man and a ruthless enforcer makes things all the more chilling.It's almost unbelievable that a film as relentless, audacious, and absorbing as Lang's The Big Heat could have been made in the context of the Hollywood studio system under the notoriously restrictive Production Code. Then again, like many of the best films from this era, maybe it's precisely *because* of the constraints of the period that the film is so effective: denied the ability to portray realistic violence or sexual content—the kind that is all but commonplace in today's films—, a filmmaker like Lang would have had to rely on the subtle power of suggestion and of well-honed characterization to generate emotional impact. That Lang was still able to make it all work so astoundingly well is surely a testament to both his and the film's undeniable greatness.